In 1991 we were beginning to get a wide enough supply of organic food ingredients to be able to create Soil Association certified organic products like baked beans and salad dressings that complied with the requirement that, to be organic, a multi-ingredient product had to have at least 95% organic ingredients. By then, at Whole Earth Foods, we were able to launch organic peanut butter, baked beans, ketchup, muesli, salad dressings and a multi-ingredient bread. We wanted to promote it because up till then most organic foods were just vegetables or fruit. So I wrote a song called “Eat Organic, Save The Planet” that urged the adoption of organic products. I recorded it and we supplied cassettes of the song to Britain’s hundreds of natural food stores, along with shelf talkers that highlighted the products. It gave the organic market a good push and sales of our newly organic products grew so much that we discontinued most of the non-organic predecessors.

Lord Northbourne - the first ‘organic’ farmer

80 years of ‘Organic’ food and farming

While since earliest times farmers have understood the importance of giving back to the land in return for the food that it provides us, the word ‘organic’ to describe this way of farming was first used by Lord Northbourne in his book ‘Look to the Land’ published in 1940. It came out at a time when industrial farming had relentlessly destroyed the accumulated fertility of millennia and sparked a debate for sustainable farming that continues to this day. But where did the inspiration come for Northbourne’s ideas? The trail leads back to the late 18th C and to the ideas of the poet and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose 1790 book, An Attempt to Interpret the Metamorphosis of Plants, laid the foundations for modern plant biology.

Two hundred years ago Goethe propounded the idea that there was a life force in plants. He saw that plants were driven by an ongoing intensification and that a ‘cycle of expansions and contractions’ shaped the plant, making either leaf, flower or seed depending on the degree of the ‘dynamic and creative interplay of opposites’. This is what underpins the harmony of the universe and the harmony of life on earth down to the tiniest life forms.

Rudolf Steiner wrote extensively on Goethe and developed Anthroposophy on the foundation of what he called Goethe’s ‘spiritual-scientific basis’ of thinking.

Goethe’s doctor was Christoph Hufeland, author of Makrobiotik oder Die Kunst, das menschliche Leben zu verlängern (1796), (Macrobiotics: the Art of Living Long). He was a naturopath who was also doctor to the King of Prussia Frederick Wilhelm lll, Schiller and Goethe, all part of the Weimar set. His ideas on human health and vitality mirrored Goethe’s observations on plant health and vitality and he was a close friend of Samuel Hahnemann, creator of homeopathy. Goethe hosted a Freitagsgesellschaft (‘Friday Society’) at which Hufeland would read from his drafts of Makrobiotik. Hufeland’s medicine envisaged a life force that should be nourished - the Hufelandist movement was largely vegetarian and inspired the Lebensreform (“Life Reform”) movement in the rest of Germany over the next century.

Steiner was an active proponent of this Lebensreform movement which sought a ‘back to nature’ way of living, with an emphasis on healthy diet and alternative medicine. In 1924 Steiner gave an agriculture course that was organised by biodynamic farming researcher Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. Pfeiffer then went on to found the 800-acre biodynamic research farm at Loverendale In the Netherlands that provided the practical proof of Steiner’s theory. So in 1939 when Lord Northbourne decided to set up Britain’s first biodynamics conference he invited Pfeiffer to run it. The resulting Betteshanger Summer School and Conference brought together a wide range of proponents of biodynamic farming. It was a seminal event in the history of the organic farming movement. A few months later Germany invaded Poland, World War ll broke out, making further collaboration difficult. A year later, in 1940, inspired by the visionary 9 days of the Betteshanger Summer School, Lord Northbourne’s book ‘Look to the Land’ was published.

It was a best seller. In it Northbourne identifies debt and ‘exhaustive’ farming as having the potential to lead to ‘the extermination of much of the earth’s population by war or pestilence.’ He points out that if the land is sick, then farming is sick and that people will be sick. That Nature ‘is imbued above all with the power of love; by love she can after all be conquered but in no other way.” In ‘Look to the Land’ Northbourne coins the term ‘organic’ to describe farming that sees the farm as an organism. “The mechanism of life is a continuous flow of matter through the architectural forms we know as organisms. The form alone has any life or any organic identity.” In this he mirrors Goethe’s writing on botany.

He wrote that to quarrel with nature makes no more sense than a ‘quarrel between a man’s head and his feet.’ He described ‘organic’ farming as “having a complex but necessary interrelationship of parts, similar to that in living things”. Although nobody had previously used the word ‘organic’ to describe this way of farming, ‘Organic’ became, in English, the accepted descriptor.

In 1943 Eve Balfour’s ‘The Living Soil’ began by quoting across several pages in her first chapter directly from ‘Look to the Land’ She founded the Soil Association 3 years later in 1946, with support from Northbourne. Her book and Northbourne’s informed the debate about the future of farming in Britain, a debate that was closed off by the Agriculture Act of 1947 where ‘exhaustive’ agriculture to maximise production prevailed. Subsidies were given to farmers who used ICI’s chemical fertilisers and farmers who refused to ‘modernise’ were threatened with land confiscation. Farming was nationalised and the organic movement was marginalised.

In Japan, Sagen Ishizuka, doctor to the Japanese imperial family, followed up on Hufeland’s macrobiotic ideas and developed “shokuiku” (“Food Study”) and in 1907 created the Shokuyo (Food for Health) movement. A shokuiku follower, George Ohsawa, subsequently published a book in 1960 setting out the principles of healthy living and called it ‘Zen Macrobiotics’.

Ohsawa knew of Christophe Hufeland and freely adopted Hufeland’s term ‘Macrobiotik’ to describe his diet based on similar principles, embodying a yin and yang approach to food. He sought out and met a descendant of Hufeland in 1958. Ohsawa’s seminal book was adopted by the emerging alternative society and inspired the natural foods movement of the 1960s that supported whole food and organic farming. The natural foods stores adhered to macrobiotic principles, selling only whole grains, eschewing sugar and artificial ingredients and supporting organic food.

So it was that Goethe’s doctor Christophe Hufeland coined the term “Makrobiotik” that drove the Lebensreform movement and inspired Rudolf Steiner to develop the anthroposophical farming principles known as ‘biodynamic, which were proven in practice by Steiner’s follower Pfeiffer. Lord Northbourne’s book gave the movement momentum and the name ‘organic.’ A Zen version of the same principles emerged in the 1960s and helped drive the natural and organic transformation of farming, diet and medicine that will ultimately restore our soils and thereby underpin the health and vitality of us all.

"Who knows himself and others well / No longer may ignore: / Orient and Occident dwell / Separately no more” Goethe

For peat's sake

2500 years ago Plato wrote about ancient Greece many years before: “... the earth has fallen away all round and sunk out of sight. The consequence is, that in comparison of what then was, there are remaining only the bones of the wasted body, as they may be called, all the richer and softer parts of the soil having fallen away, and the mere skeleton of the land being left.”

At a remarkable mid-June gathering at Morvern in the West Highlands I read the above excerpt from Plato, who was describing Greece before farmers totally screwed it up. The theme of the conference was ‘Soil Matters’ and it brought together leading soil scientists, artists, musicians, government and NFU officials, land managers and others with an interest in soil and sustainability. It was hosted by the Andrew Raven Trust, a trust established in memory of his profound influence on Scottish land management and environmental issues. Because we were in the Highlands the role of peat in climate change and sustainability was a topic. Peat has a deep resonance with the spirit of Scotland - I’m not talking about whisky here but about peat bogs.

The Scottish landscape has seen some hard times - the Clearances led to populated areas seeing the longstanding human residents sent off to Glasgow or America or Australia, to be replaced by deer and sheep. Now the Scots are recreating the marvellous environment that reflects the levels of rainfall that typify the region and rebuilding rural populations living in harmony with this unique environment. A surprising number of the new migrants are from England.

Misguided post-war policy gave indiscriminate tax incentives to forestry. Trees were inappropriately planted on peatlands, the bogs dried out, the ecosystem collapsed. Now there are active peat bog restoration projects all over Scotland and the benefits to environment and climate are inestimable. A peat bog can compete with a woodland in the amount of carbon dioxide it takes out of the air and stores permanently in the depths of the earth. Scotland’s peat bogs are making a huge contribution to mitigating climate change and we still don’t pay them a penny for doing it. With carbon pricing on the horizon that could change. If the carbon price is £50/tonne CO2 then an undisturbed peat bog could earn its owner £2-300 per hectare per year. That’s more than you could make by cutting the peat for fuel or compost.

Peter Melchett, the late Policy Director of the Soil Association, dreamed of the day when peat use was phased out completely from organic farming. A 2010 Government deadline for removing peat from horticulture was quietly extended to 2020 and now neither Defra nor the EU have any concrete plans to phase out peat use - the pressure from horticulture is too strong - tomato and vegetable growers are a powerful lobby.

So, while the Scots are diligently restoring peat bogs the rest of the world is still digging it up to save microscopic amounts of money. We deserve to die if we can’t do anything about this insanity. Vast peat bog areas of Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Canada are being mined on an industrial scale to supply vegetable growers. There have been attempts to phase peat out of organic and conventional production. ‘Peatless peat’: compost blends of coir, composted shredded bark, biochar and green waste perform just as effectively but cost a tiny bit more. They have a vastly lower carbon footprint. The organic movement sees itself as superior to other growers and farmers but the use of peat is one area where we must hang our heads in shame. Every principle of sustainability is contradicted by the use of peat;: it takes tens of centuries to replace; it turns into carbon dioxide within a year or two of being used; and it destroys biodiverse habitats. Growers feel under tremendous pressure from supermarkets to cut costs in any way possible and peat is cheap.

Alternatives that don’t devastate the environment can do the job just as well, they just cost 1/2 a penny more than peat for a seedling plant. A tomato plant can produce 50 tomatoes, so that’s 1/100 of a penny that is saved by using peat to grow tomatoes. Screw the planet, let’s save a penny per 100 organic tomatoes.

It is time for the organic movement to revisit its founding principles, look to the Scottish example and drive a worldwide movement to restore peat wetlands and make peat use extinct before peat use makes us extinct.

Good health begins with food

Craig Sams invites us to reflect on the achievements of Dr Scott Williamson and Dr Innes Pearce, who set up the Pioneer Health Centre in an effort to steer both individuals, and society as a whole, towards better health.

Back in the 1930s Dr Scott Williamson and his wife Dr Innes Pearce decided to do something about the dire health of the British public. They found a location in Peckham, which was one of the poorest districts of London, where they could put into practice their ideas about how a healthy society could be founded on healthy individuals. They believed that individuals who were empowered could take control of their diet and their environment and help build a better world.

They set up the Pioneer Health Centre and soon built a modern building with a swim- ming pool and facilities for education. It was immensely successful. Local people had to pay a shilling a week (5p) to be members, and it was worth every penny. People who attended the centre experienced a multiplicity of benefits including: robust good health; kids doing better at school; more stable marriages; empowered women; gainfully employed men; and less alcohol consumption.

Beating the five evils

The Pioneer Health Centre was well known and admired. In 1943 William Beveridge issued a Government report that mapped out the post-war plans to create a welfare state and a National Health Service. The health of the nation had never been better than during the war, when bakers could only make brown bread, and homegrown vegetables were widely eaten. Beveridge predicted in his budgets for the NHS that the cost through the 1950s would steadily decline as there would be hundreds of health centres based on the example of the Pioneer Health Centre. These would impact on what he called the ‘five evils’: squalor; ignorance; want; idleness; and disease. These evils would be beaten with: better sanitation and indoor plumb- ing; better education; a fair social system; jobs for all; and a positive attitude to health.

Let us always remember Scott Williamson and Innes Pearce who proved, almost a century ago, that good health begins with food, and that you can be your own best doctor

There was huge resistance from the medical establishment to the idea of ‘health centres’ where people organized things themselves. At the Pioneer, members organized their own sporting, cultural and social activities, and engaged in physical exercise, health workshops and periodic medical examinations. This bot- tom-up approach was anathema to the British Medical Association. To get doctors’ support for the NHS, the Government had to go top-down and set up a state-run Ministry of Health. The National Health Service concept was upended to become a ‘National Disease Service’, with doctors, pharmaceuticals and surgery in charge. Beveridge was furious, but powerless.

A mirror of society

Scott Williamson was a bit too radical for his time. He wrote that Peckham was an ideal mirror of British society, with all classes of people as well as ‘the scum at the top and the dregs at the bottom’. His secretary was Mary Langman, who went on to work with Eve Balfour. His wife, Dr Innes Pearce, co-founded the Soil Association with Eve to fight for a similar whole- some bottom-up approach to food production. But the Government owed a huge debt to ICI, who had made the nitroglycerin explosives that helped win WW2. ICI had factories that could easily be switched to nitrate fertilizer production. The Ministry of Agriculture began to subsidize chemical fertilizer and threatened to nationalize any farms that stuck to the old ways. So the war for human health and soil health was won by vested interests who profited most when people were sickly and soils were degraded. The Pioneer Health Centre closed down in 1950 due to a lack of funding, despite its success. The first Wimpy Bar opened in 1954.

The Soil Association continued to fight on behalf of our soils and human health. On 4 October 2002 it held a conference entitled Education Education Education. I gave the keynote speech and used the Peckham project as an example. The Soil Association set up Food For Life and concentrated on raising the quality of school dinners. It’s been an incredibly successful programme and has no problem attracting funding, though not from Government sources. Now, organic freshly prepared wholesome food is not just widely available in schools, but also in hospitals and retirement homes. Better food is now everywhere.

Let us always remember Scott Williamson and Innes Pearce who proved, almost a century ago, that good health begins with food, and that you can be your own best doctor.

Organic Integrity

One of the early ‘miracles’ of genetic engineering was the Flavr-Savr tomato. The edited gene enabled the tomatoes to be picked at peak ripeness and then the ripening process would be stopped and the tomato would be yummy. As always with genetic engineering, there were unforeseen complications. When the first year Flavr-Savr tomato crop in 1994 was shipped to supermarkets across the USA they arrived in terrible condition. Nobody had tested them on a road journey. The slightest vibration on the truck journey and the tomatoes became inedible mush. What to do?

The entire tomato crop was harvested, pureed and canned in an attempt to cut the horrendous losses. Now who would buy the cans? No American supermarket would touch the stuff, but Safeway and Sainsbury’s bought the lot. The cans were proudly labelled ‘Made with Genetically Engineered Tomatoes’ and sold at 2/3 of the price of Italian non-GMO tomato puree. It was great PR for GMOs: ‘Wowser! thought the consumer - these GMO tomatoes are going to knock loadsamoney off my grocery bill, so I’ll have more to spend on necessities like beer, fags and cheap disposable clothing!’

Calgene, who launched the Flavr Savr, went bust and taken over by Monsanto. Around the same time the introduction of GMOs into Europe was a done deal. Directorate General Agri, or ‘DG Agri,’ the EU Commission department (who really decide what the rules are in the rotten and corrupt Common Agricultural Policy) had already promised the biotech barons they needn’t worry.

When we realised what was happening Richard Austin of Rainbow Wholefoods organised the wholefood wholesalers and retailers to dig in their heels against GMOs. With the Soil Association we lobbied to require that GMO ingredients be labelled. As Safeway and Sainsbury’s had already proudly done it on front of pack, this was a relatively easy win and DG Agri let it pass, not realising it was a fatal strategic mistake until too late. GMOs were dead in the water. If a consumer saw ‘Genetically Engineered’ on the label they would put it back on shelf, no matter how cheap.

In September 1999 Patrick Holden and I met with the top people of Monsanto under the auspices of the Environment Council. Monsanto wanted to understand how everything had gone so horribly wrong with their planned GMO blitzkrieg into Europe.

Patrick and I explained organic principles and how they were at total variance with the ideas of genetic modification. I kept a note of the meeting that included this line:

This opening exchange was the first and most fundamental revelatory experience for them. They had never really understood these most basic organic principles.

It was appalling how little they understood about organics. Once they realised what an obstacle to the rollout the organic world represented they took us seriously.

Subsequently there has been an extended campaign of disinformation about organic food running with various fallacious arguments: we would have to cut down rain forests to get the extra land to grow organically; e.coli O157:H7 in lettuces is higher in organic food; organic farmers use terrible pesticides; GMOs are safer than organic; you can’t trust organic certification.

Forbes Magazine was a good vehicle for this kind of crap. Dr. Henry I. Miller has written about how organic food is a ‘deceitful, expensive scam’ and ‘the colossal hoax of organic agriculture.’ Forbes finally fired him when they found out one of Miller’s articles was written by Monsanto. Miller helped Philip Morris organise a global campaign against tobacco regulations and wrote that nuclear radiation is good for your health. He wrote a blistering attack on the World Health Organisation when they pronounced Roundup a ‘probable carcinogen.’

Burson Marsteller are the PR company that Monsanto use whenever they have an environmental disaster - they are expert at making bad stuff look ok. And at making good stuff look bad. When there was an anti-GMO demo in Washington they hired, for a $25 honorarium, counter-protestors with signs saying: ‘Biotech Saves Children’s Lives.’

There’s a well organised misinformation campaign out there about how you can’t trust organic certification. Meanwhile the Soil Association has been asked by China to certify organic producers there because of its globally-respected integrity. A leading oats supplier sued the Soil Association, backed by Defra and another certification body, because the Soil Association refused to accept documentation on oats that tested for pesticide residues at levels well above ‘spray drift.’ Now all certification bodies must sample for pesticides and have the right to reject products that fail the test. Belt and Braces. Food You Can Trust.

Harmony in food and farming

The groundbreaking Harmony in Food and Farming Conference explained why a sustainable food culture sits naturally at the heart of an inspiring philosophy for harmonious living, says Craig Sams

In 2010 a book called ‘Harmony – A New Way of Looking at Our World’ was published. Written by HRH The Prince of Wales along with Tony Juniper and Ian Skelly, the book set out a coherent philosophy of harmonious living for communities and society, along with inspiring examples and a roadmap to a better future. It was inspired by the philosophy of the Stoics of Greece, while acknowledging Taoism, Zen and the Vedic texts. The book aims to re-engage the thinking that sought harmony with the order of the cosmos and a reconnection with Nature. It covered subjects like architecture, urban design, natural capital, deforestation and farming.

Inspired by the book, Patrick Holden, former director of the Soil Association and founder and Director of the Sustainable Food Trust, organised a conference in Llandovery Wales on July 10-11. The aim of the conference, entitled ‘Harmony in Food and Farming‘ was to put meat on the bones of the Prince’s book and to map out a way forward for agriculture and food production that resonated with the principles of harmony.

The conference kicked off with an inspirational keynote speech and then looked at a range of subjects, with key speakers from all around the world. Rupert Sheldrake led a session on ‘Science and Spirituality,’ Prof Harty Vogtmann moderated a session on ‘Farming in Harmony with Nature.’

A session on ‘The Farm as an Ecosystem’ saw Helen Browning, director of the Soil Association, describing her new agroforestry project that encourages happy chickens to range free in a productive orchard of apple trees.

A session entitled ‘Sacred Soil, Sacred Food, Sacred Silence’ highlighted the extent to which faith communities put harmony first in developing their food production systems.

A session on ‘Agriculture’s Role in Rebalancing the Carbon Cycle’ was my opportunity to shine with a presentation entitled ‘Capitalism Must Price Carbon – or Die’ in which I showed that if carbon emissions were priced into farming organic food would be cheaper than industrial food and we’d get the extra benefits of biodiversity, cleaner water and regenerating soils – all themes familiar to readers of my column in NPN. Then Richard Young set out the case for livestock farming that could operate harmoniously within our climate constraints and Peter Segger described his carbon-sequestering vegetable growing operation, which was a fascinating field trip that afternoon.

A session on animal welfare sought to see a way forward to keep animals happy during their short lives and to make that final moment of betrayal as pleasant as possible, with reference to examples and a deepening of the understanding of the sacred relationship between the animals we rear with care and then kill.

Patrick Holden learned his farming at Emerson College and is empathetic to biodynamic principles. A session on Harmony and Biodynamic Agriculture showed how the ideas of Rudolf Steiner resonate with the Harmony philosophy. At a reception the evening before the conference I mentioned to HRH that our original Zen Macrobiotic company was called Yin Yang Ltd and that our brand was Harmony Foods and that we had taken our philosophical guidance from Zen Buddhism and Taoism, unaware that the Stoic philosophy or Greece was on the same page. He commented that the Egyptians had laid the philosophical foundations for the Stoics. I wondered at how a way of thinking that had arisen simultaneously in China, India, Greece and Egypt was now guiding the effort to restore balance to our dysfunctional and unsustainable world.

The conference was attended by delegates from every continent and the closing plenary session included individual delegates describing how the conference had affected them. It was very moving stuff and helped us realise how much we all had been changed by two days in Wales. Patrick stood up to finalise the session and received a prolonged and much-deserved standing applause. The conference was a remarkable achievement. It is now the job of the Sustainable Food Trust to build on its relationships with the organisations that were represented at the conference, capture the momentum of the gathering and give impetus to the movement for harmony, regeneration and an end to the war on Nature that has brought us so dangerously close to disaster.

The proceedings of the conference, filmed and edited, can be seen on the Sustainable Food Trust website.

My Sugar Odyssey

Now that the Government is slapping a tax on soft drinks I am going to indulge in a reminiscence of my troubled relationship with sugar, health and food. My first job, as a 7 year old kid, was to scour the streets of a Pittsburgh suburb called Bridgeville, collecting discarded soda bottles and taking them to my aunt Gloria's store to collect the 2¢ deposit refund. At that time a soft drink was 10¢, so the drink was 8¢ and the bottle deposit was 2¢ and people still threw the bottle away. The deposit didn't make much change in behaviour. When people wanted sugar, they paid what it cost.

I didn't really have much appetite for sugar for most of my childhood, our mother was pretty strict about it. I remember the day in 1953 when confectionery came off the ration in the UK and some schoolmates emerged from a sweet shop with a bag of humbugs they'd just bought without having to cajole their mother to come along with her ration book. The nation went mad for sugar and the Government had to put it back on rationing until supplies recovered.

It was in 1965, when I was in Afghanistan, recovering in Kabul from a serious case of hepatitis, enhanced with dysentery, that I understood sugar. My liver was on strike and the doctors told me that I should eat lots of simple sugary food to keep my blood sugar levels up. The dysentery told me otherwise: I knew from an early bout in Shiraz, that a diet of unleavened whole meal flat bread and unsweetened tea was the key to stopping the runs. So I tried it again and the dysentery cleared up in 2 days. Amazingly, so did the hepatitis. My liver stopped throbbing with pain and the whites of my eyeballs went from greenish yellow to something close to white.

That autumn, back in Philadelphia, I adopted the macrobiotic diet which forbids sugar. My health rose to an even higher level and I haven't once needed to see a doctor since about my health. After a few years I was able to reintroduce alcohol into my diet but tried to keep a lid on sugar.

In 1966 I was in London, aiming to open a macrobiotic restaurant and study centre. From December, I was a regular at the UFO Club, where proto-hippies would listen to the Pink Floyd and then buy macrobiotic food that my mother had helped me make. My little band of macrobiotic missionaries would then explain to people trying this strange food that brown rice was good for you and sugar should be avoided. I opened a little basement restaurant in Notting Hill in February 1967. Yoko Ono was one of our first customers, as she knew about macrobiotics from Japan.

We made bread without yeast, macrobiotic-style and I imported books like Zen Macrobiotics by Georges Ohsawa (Nyoiti Sakurozawa) that were sold in Indica Books, the bookshop owned by Paul McCartney and Barry Miles.

Macrobiotics avoided yeast for the same reason they avoided sugar: too much could cause dysbiosis of the gut flora. Meanwhile the American Medical Association called macrobiotics a diet that 'could lead to death'

Dr. Arnold Bender, Britain's top nutritionist, said white bread was the most easily digestible and nutritious bread you could eat, slapping down the wholemeal alternative as too slow to digest and with lower nutrients, because wheat bran fibre has no protein and carbohydrate.

In 1968 I had to leave Britain and my brother Gregory opened a larger restaurant in Bayswater called Seed.

None of the desserts were made with sugar - a touch of salt was enough to bring out the sweetness of the apples in the crumbles. At festivals like Glastonbury and Phun City we would serve up porridge to the festival goers and got into trouble at one festival as our customers would head off to an adjoining catering tent to get sugar to sprinkle on their porridge and muesli. We had a shop on the Portobello Road called Ceres Grain Shop that sold all the whole grains, beans, seeds and organic vegetables but the only sweet thing we sold was Aspall organic apple juice.

I wrote a book called About Macrobiotics in 1972 that was translated into 6 languages and sold half a million copies where I wrote: "If sugar was discovered yesterday it would be banned immediately and handed over to the Army for weapons research."

We were hard core. My kids didn't dare even ask for sweets - they might sneak them with friends at school but would destroy the evidence before they got home.

We didn't believe in refined cereals either - no white flour or white rice touched our lips. Our macrobiotic food wholesaling company Harmony Foods introduced the first organic wholegrain rice. In 1973, with other pioneering natural food companies we wrote the manifesto of the Natural Foods Union. We promised each other not to sell sugar or any products containing sugar or white flour or white rice. We were committed to developing organic food sources which were then rare. Signatories included Community Foods, our own Harmony Foods and Ceres Grain Shop, Haelan Centre, Infinity Foods, Harvest of Bath, Anjuna of Cambridge and On The Eighth Day in Manchester.

We published a magazine called 'Seed - The Journal of Organic Living' that had cover stories with headlines like "Garbage Grub - How The Poor Starve on Rich Foods" and a story on Britain's future which set out a dystopian vs Utopian vision where on one side people were clamouring for 24 Hour TV and More Sugar. On the other they were tending goats and living in countryside communes eating whole natural foods.

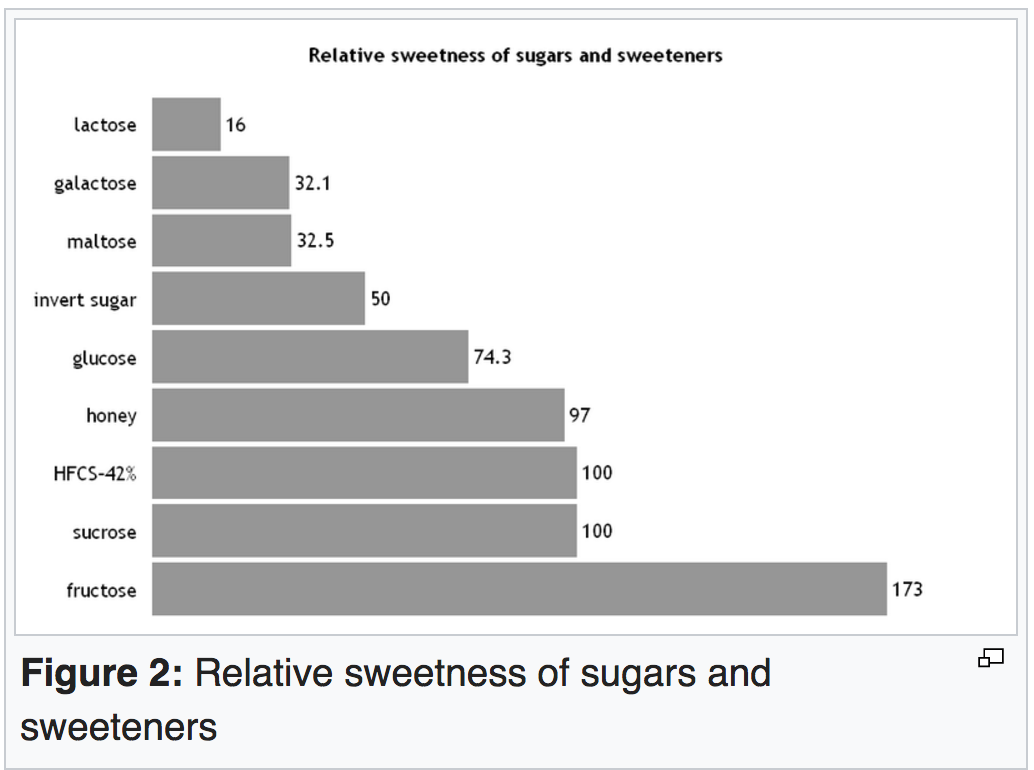

Then in 1977 I worked out how to make jam using apple juice. Being higher in fructose it was possible to make a jam with a lot less sweetening, so it tasted light and fruity. They were 38% sugars from fruit when other jams were 65% sugars from sugar cane and fruit. Whole Earth jams were an international success as they reached out to the increasing numbers of sugar avoiders in the UK, Europe and North America.

However our sales met stiff competition from much sweeter jams that used fruit juices like grape juice that were higher in glucose than white sugar and they used a lot of it, to match the sweetness of regular jam. Our moral restraint cost us sales to these much more sugary jams. However we also used apple juice to sweeten other products, marketing baked beans, soft drinks and salad dressings. Even our best selling Whole Earth peanut butter contained a touch of concentrated apple juice to make it taste more mainstream.

Then, while searching for another source of organic peanuts I connected with Ewé tribal people in Togo, West Africa, who grew delicious peanuts as part of an organic crop rotation. Unfortunately the peanuts failed our aflatoxin tests but the farmers also grew organic cocoa beans. There was no organic chocolate on the market at that time so I got a sample made up of 70% solids chocolate made with organic cocoa beans.

We called it Green & Black's and launched it in September 1991. It was the first time I had sold a product containing real sugar from sugar cane. It was the first organic and the first 70% and the first chocolate with a transparent supply chain. So we put a sugar warning on the label – I think this is the only time that any company has done this. It read: “Please Note: This chocolate contains 29% brown sugar, processed without chemical refining agents. Ample evidence exists that consumption of sugar can increase the likelihood of tooth decay, obesity and obesity-related health problems. If you enjoy good chocolate, make sure you keep your sugar intake as low as possible by always choosing Green & Black’s.”

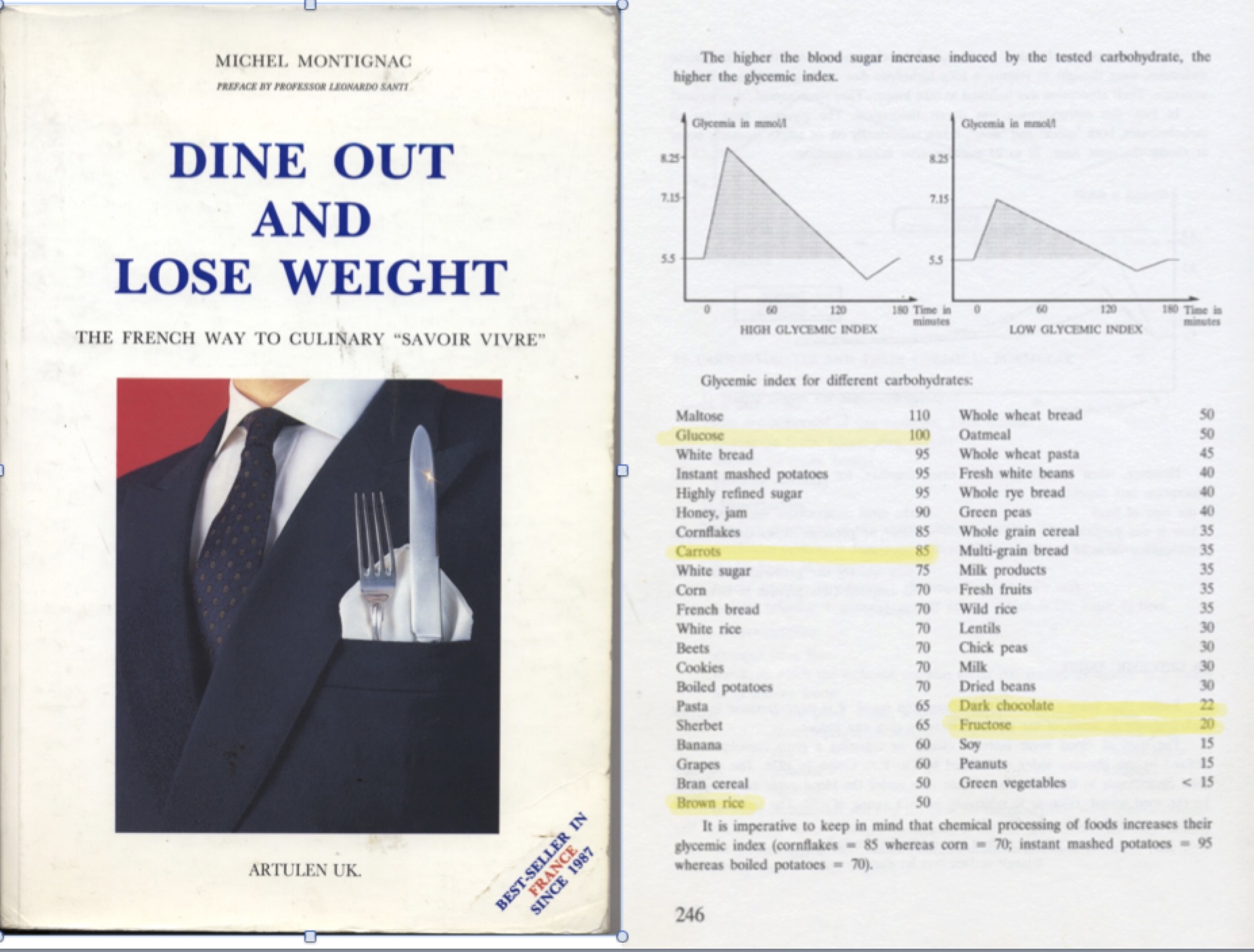

How did I square this with my conscience? Well, a French author called Michel Montignac had written a best-selling book called 'Dine Out and Lose Weight' that was one of the first places the idea of glycemic index had been in print. In his book 70% dark chocolate had a ranking of 22 on a scale where sugar was 100. Brown rice was at 50 and carrots at 70. Fructose was at a mere 20.

Two of our best Whole Earth foods customers, Community Foods and Planet Organic, flat out refused to stock Green & Black’s because it contained sugar. Tim Powell at Community said: "Craig, you were the one who got us all to not sell sugar back in the day - we can't stock this." (they came around eventually)

I mentioned earlier that apple juice was higher in fructose. The crystals of fructose and glucose, the two monosaccharides that make up a sugar molecule (sucrose), have exactly the same chemical formula: C6H12O6. So what's the difference between glucose and fructose?

If you beam a light into the glucose molecule it bends slightly to the right. If you beam a light into a fructose molecule it bends slightly to the left.

If you put a given amount on your tongue the fructose will taste more than twice as sweet as the glucose

If you eat the glucose it raises your blood sugar within 20 minutes. If you eat the fructose it has almost no impact on blood sugar.

If you eat a given amount of sugar the glucose half hits your bloodstream, the fructose half passes down your digestion and is eventually turned into glycogen or into fatty acids. These provide an energy source that is managed by the body rather than just absorbed in the way that glucose is. So Lucozade, a glucose drink, was marketed on the premise that ALL the sugar - because it was glucose - got through to you immediately and that this would 'speed recovery.' It was a deluded proposition, but it captured the fact that you got twice as many sugar bangs for your bucks.

If you have apple juice, there is more fructose than glucose or sucrose, so you don't get the same 'hit' as a lot of the sugar takes a different metabolic pathway. Corn syrup is about 80% glucose. Because glucose isn't very sweet on the palate, you have to use a lot more of it to get to the same level of perceived sweetness. This increases the load of glucose to satisfy the taste for sweetness, with a resulting harsh impact on the blood sugar level. 'High fructose corn syrup' has a higher level of fructose, between 45 and 55%, so it is used in industry because it has nearly the same glucose/fructose balance as white sugar. It's healthier than ordinary corn syrup, as measured by blood glucose impact.

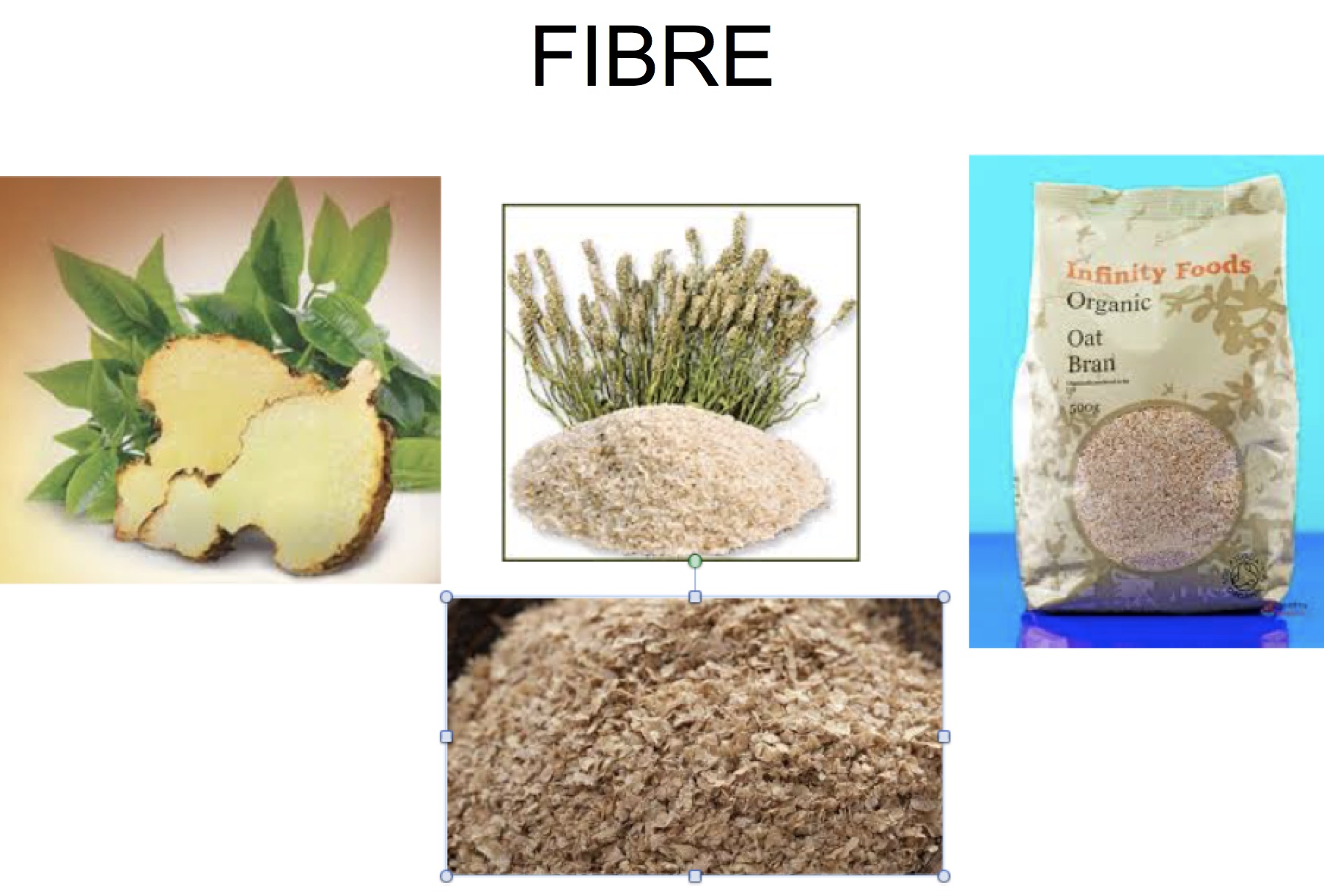

If you really want to get all the glucose right away then it's best to drink it on an empty stomach. All sugars are not absorbed equally. If you eat dessert before you eat a meal the sugar will get into your system very quickly. If you eat dessert after a meal then it has to work its way through the previously ingested food and has a longer exposure time to your digestive bacteria. The higher the fibre content of your meal, the longer it takes for the sugar to be absorbed. There are some fibres that are particularly good at delaying the impact of sugar. One of these is psyllium seeds. Not only do they delay sugar absorption by up to an hour or so, they also bulk up, by absorbing water, your intestinal contents, helping regular passage of food. Glucomannan also has this property as does oat bran. Wheat bran doesn't absorb water to the same degree, but it absorbs sugar and delays its release in digestion. The longer it takes for sugar to be absorbed, the less impact it has on blood glucose level.

There are also foods that help with insulin production and that reduce insulin resistance, thanks to the presence of chromium. Chromium-rich foods include black pepper, broccoli, bran, brown rice, lettuce and green beans. The leaves of the white mulberry are considered particularly effective at delaying sugar absorption, containing a component called reductase.

There are also co-factors that accelerate the rate at which your body metabolises sugar or that challenge your natural regulatory mechanisms. These can increase the likelihood of a blood sugar drop, known as hypoglycemia, the symptoms of which are fatigue, depression and a craving for more sugar.

These co-factors include:

Coffee and, to a lesser extent, other caffeine stimulants like tea, maté, cola, guarana and cocoa. They will increase the rate at which the brain burns sugar. Small wonder then that when you purchase a cup of coffee there is always an extensive display of white flour and sugar sweetened products to tempt you. Your body knows it's going to be short of sugar after you drink the caffeine, so you instinctively go for the antidote to have on hand as you consume the stimulant.

The liver is the main organ, along with the pancreas, that regulates your blood sugar level. As blood flows through the liver its glucose level is measured and, if it needs topping up, the liver dips into its store of glycogen, converts it to sugar and drip feeds it into the blood.

Alcohol When you drink alcohol the liver prioritises dealing with what it perceives as a poison and puts dealing with blood sugar on the back burner. The pancreas also finds it harder to produce insulin and regulate insulin levels when it also has to deal with the presence of alcohol.

Dope is another culprit. When you smoke marijuana it increases the blood level in the brain by an estimated 40 millilitres. This increases the amount of sugar available for the brain to burn and this heightened mental activity is part of what is called being 'high.' However this increased usage of sugar makes it harder for the liver to keep up and the resulting drop in blood sugar is the symptom known to dope smokers as 'the munchies' - an irresistible craving for sweet foods.

Glyphosate or ‘Roundup’ - research has shown that ultra low doses of Roundup consumed over time leads to fatty liver disease. Fatty liver doesn’t function very well and therefore makes it harder for the blood to maintain the right glucose levels. Farmers spray Roundup at the end of wheat harvest to kill off the wheat plants. When the plants realise they are dying, they frantically make as many babies as possible, i.e. wheat grains. This is reflected in an increased harvest quantity, but ensures that every loaf of non-organic bread or other flour product contains a low dose of Roundup residue.

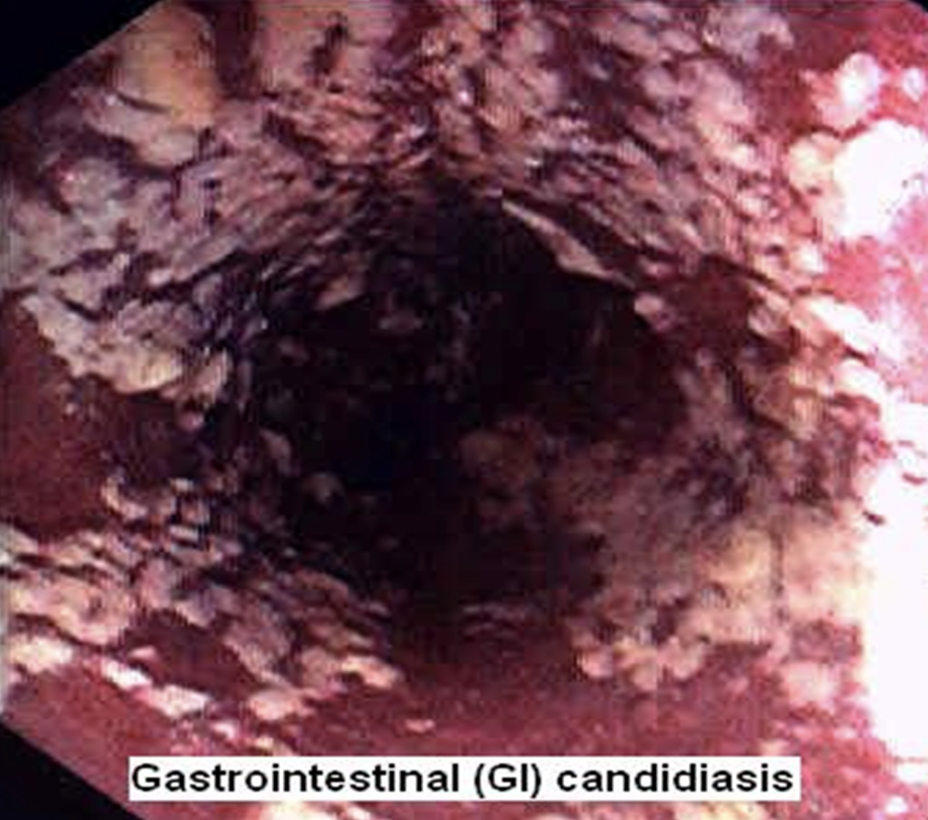

Antibiotics also can lead to powerful cravings for sugar. If antibiotics are ingested, they don't just target the disease bacteria they are taken to cure. They wipe out the beneficial microbes that are our healthy population of gut flora. That's why it's advisable to consume yogurt or sauerkraut or other foods rich in lactobacilli to replace these important microorganisms. It's also a good idea to eat foods rich in fibre to help the equally important bifidobacteria which are a pivotal part of the immune system in the large intestine. A small population of these and other beneficial bacteria are always present in your appendix. The appendix is the body's equivalent of a survivalist's food store, a place, at the junction of the small and large intestine, where, once the antibiotics are finished, the intestines can be repopulated. Antibiotics can not kill off the tiny population of yeasts that are a part of the wider bacterial community of the gut. But once the dominant lactobacilli and bifidobacteria are out of the way, yeasts quickly mutate into a fungal form, candida, a sticky white slime that imbeds itself firmly in the walls of the intestines.

There is an established communication between the gut and the brain and this is a vital part of our food choices, what smells nice, how hungry we feel and also what antibodies the gut flora need to produce to combat pathogens - what we call our immune system. When candida gets a grip, like a Russian hacker taking over the CIA, it takes over the communication channel and sends a message to the brain demanding more sugar. The more of these foods it gets, the more powerful it becomes and the more successfully it outcompetes the beneficial microbes that are trying to repopulate the gut after the antibiotic A-bomb has exploded. Getting rid of candida is not easy, but there are ways to do it:

Saccharomyces - these little microbes compete effectively with candida for sugar, thereby holding back the growth of candida and starving them out. They come in capsule form

L-glutamine - this also attacks candida. Also in capsules

Fasting - I often say that 'breakfast is the most important meal of the day…to skip.' This is because by the time you wake up in the morning the liver's reserves of glycogen are low and it's time to convert fat into glucose to keep the blood sugar level up. This keeps sugar away from the gut and the candida, which then die off. If you eat a carbohydrate-rich breakfast, perhaps with a glass of fruit juice, the sugars keep the candida topped up and maintaining or expanding their population, perhaps even migrating to other parts of the body such as the vagina or skin. Starve them out by fasting for 17 hours a day.

Colonic irrigation - pumping water into the large intestine and then pulling it back out removes a lot of candida.

Lactobacillli - probiotics. Eating foods rich in lactic acid and consuming spores of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria helps to create ideal conditions for repopulating your beneficial gut microbes that compete with candida

Inulin - this is a molecule that is made of a long string of fructose molecules strung tightly together. It is indigestible and counts as fibre but when it gets to the large intestine the wonderfully beneficial bifidobacteria feast on it and increase their numbers by the billions.

Good food sources of inulin include whole grain wheat and rye, shallots, onions, leeks, chicory root and the white part of chicory leaves and Jerusalem artichokes. These are all valuable nutrition for the gut microbes. Inulin powder, extracted from chicory roots, is a concentrated source.

Candida puts pressure on you to consume the sugar it needs and urges your brain to crave refined flour products, dairy, wine, beer and sugar. It's not just antibiotics that give candida its supremacy in the gut, it also benefits from hormone replacement therapy, the birth control pill, steroids and hydrogenated fat.

Vinegar also plays a role in sugar metabolism. Nobody’s quite sure why, but if you take 2 tablespoons of vinegar before a meal the increase in blood glucose later is 34% lower than if you don’t take vinegar. That’s a big difference as it keeps the level at a level less likely to be stressful.

Lactate

The brain consumes glucose as the energy source that enables neurons to fire. It's the 'carb' or 'carbon' in 'carbohydrate' that is the energy source. Oxygen feeds the fire of carbon in the body, which is why we breathe. So we are like a coal fire, burning carbon to keep ourselves warm and to enable our brains and bodies to function well. However, lactate is another rich source of carbon for the brain. If there is lactate in the blood then the neurons in the brain will preferentially coat themselves in it rather than with glucose. It's as if lactate is like gas fuel for the brain, glucose more like coal or wood. Where do we get lactate?

When our digestive system has a healthy population of lactobacilli they will compete with candida and other microbes that are eating starch or sugar and a by-product is lactate

When we walk, run, jump or dance or do any exercise our muscles burn glucose and give off lactate.

At some point in evolution our brains evolved to function best on the super fuel of lactate in preference to glucose. Glucose for the body, lactate for the brain.

So exercise is really important as it provides a better quality of energy for the brain - lactate also delays brain ageing and neurodegeneration. The heart and liver use it, too. Insulin function works much better too if there has been exercise and lactate production. This is why exercise is increasingly being used as a cure for pre-diabetic conditions and for curing Type 2 diabetes in many cases.

Plato wrote: 'I fast for greater physical and mental efficiency'. Kellogg's say 'Breakfast is the most important meal of the day." Who to trust on this? Everyone has a different metabolism, but they all have the power to change bad habits.

Metabolic Syndrome is the name for the multi-symptom disease that is typical of modern sedentary people.

It's also known as 'Sitting Disease.' If a person gets up in the morning, sits down for breakfast, then sits in a car or on a train or bus, then sits at a desk or an assembly line and then sits down to return home to sit down to eat a meal and then sits watching television or enjoying social media they lay the foundations for Metabolic Syndrome

Contributing factors are

Inactivity/laziness (Both cause and effect but a natural human condition)

Overeating - large food portions of food low in nutrients

Stress

Pesticides - these have a hormonal effect as well as being mildly toxic

Processed denatured food that is low in fibre

Hydrogenated fat - harms the circulatory system, reducing blood flow

Sugar and refined cereal such as white bread and low fibre breakfast cereals

Television, electronic games and sitting at computers.

So what's the answer?

Our Government has one solution for everything: Tax it.

A tax on soft drinks will have little impact as the appetite for sugar is not responsive to pricing. If your candida want sugar or you are on a cycle of high and low blood sugar you don't give a damn what the cost is of a soft drink. It's the cheapest form of sugar already and a tax won't make a difference. You get more sugar in a chocolate brownie than in a can of Coke and a brownie costs at least 3 times as much. The best selling soft drink in Britain is Red Bull. It costs double the cost of Coke and has just as much sugar.

A tax will help in one way though: The Government currently subsidises sugar beet farming and sugar production to the tune of £250 million per annum. A sugar tax will raise an estimated £400 million. So the soft drinks tax will neatly subsidise the taxpayers money that goes to sugar producers. How smart is that?

There is a far more intelligent alternative. Researchers studied a group of 46,000 people in a Japanese city who were over 48 years old. They measured their blood sugar, blood pressure, lung function and other measures of health and then recommended actions to rectify any problems before they became serious diseases. Not all of them complied, but enough did to make a difference. They became ill less often and therefore cost the health system less. The estimated average saving came to £200 per person per year.

In the UK, with 26 million people over the age of 48, that would be a saving to the NHS of £5.2 billion every year. Why don't doctors and pharmaceutical companies recommend it? Why don't wine makers discourage wine drinking? Why don't car makers urge walking instead of driving? No business likes to lose its customers, even the caring professions.

In 2011 the Soil Association applied for and won a £17 million National Lottery grant to initiate its Food For Life project. It was a huge success, with schools coming in at Bronze entry level and working up to Gold, where they offer a significant proportion of school meals that are organic, locally sourced and freshly prepared on the premises. There are now 2 million school dinners a day served under the Food For Life Programme. A lot of those schools have stopped serving desserts on some days a week. These kids perform better and learn something really important: you are what you eat.

Those kids will fare better in life, but we have a couple of generations who got the worst of crap food, hydrogenated fat (recommended by doctors), exposure to lead and pesticides and other environmental toxins. They are the ones who need help. Diabetes levels are already dropping in the Western world as more people eat more wholesome food and exercise a lot more, but there is still work to be done. A soft drinks tax is pathetic when you consider what the government could be doing to support healthier lifestyles

Change begins with the individual and it's about education. If people are junk food junkies they will always find junk food. Trying to reform the food industry, which is responding to demand that arises from a multiplicity of causes, is to fight the wrong battle. If we change demand then supply will follow.

The new science of epigenetics informs us that acquired characteristics can be inherited. The unhealthy acquired characteristics of previous generations has been one factor in the increase in autism, birth defects, hereditary diabetes and other diseases, food allergies and other developmental problems. But we need not despair, this is already being turned around and future generations can look forward to even better food produced in a cleaner environment to make healthier happier people, whose babies will be even healthier and happier. We know more now about these factors than we ever did before, so we have the power to evolve positively.

Dark Act

We have Sainsbury’s and Safeway to thank for the fact that there are no GMOs in our food, (though still in animal feed).

One of the first GMO foods to hit the market, back in 1995, was the Flavr-Savr tomato, created by a company called Calgene. The idea was that that tomato would stay fresh on the supermarket shelf for longer. Nobody checked how it travelled and the first shipments to American supermarkets ended up soggy and bruised due to some unforeseen aspect of genetic engineering and despite all the research showing no evidence of health risks.

Tomato growers in California weren’t happy but the huge planting of tomatoes in 1996 got turned into tomato puree and was sold in tins at Sainsbury’s and Safeway at a considerable discount to the normal tomato puree price. In other words, it was dumped on the British market to try to salvage a GMO disaster. The supermarkets proudly labelled the puree as ‘Made with Genetically Engineered Tomatoes’ and consumers, who had never heard of GMO, just bought them because they were so much cheaper. Then in 1998 Dr. Arpad Puztai, one of Britain’s most renowned and trusted experts on food safety, spoke out on TV about his research on the dangers of GM potatoes. The rats had shrinking brains, livers and hearts and he said he wouldn’t eat a GM potato unless more research into its safety was completed. Puztai was promptly sacked from his job at the Rowett Research Institute and gagged, with the threat of losing his pension. Then they sacked his wife. This happened allegedly after Monsanto phoned Clinton who phoned Tony Blair who phoned the heat of Rowett Professor James and told him to gag Puztai. Puztai’s career was ruined, he had a couple of heart attacks and continued to campaign for his research to be duplicated, which has never happened. The Government set up a ‘Biotechnology Presentation Group’ to try to mask the reality about GMOs.

But it was too late. The Soil Association and its European counterparts lobbied strongly for labelling of GMOs and got their way. After all if it was good enough for Safeway and Sainsbury’s customers, what about everyone else? Labelling was agreed at an EU level and nobody ever tried to sell a GM product again. The public were on high alert after the Puztai scandal and weren’t going to be duped.

In the USA it was different. Americans didn’t know what GMOs were, although they were in their corn chips and other staple foods. When the realisation came the Organic Consumers Association campaigned for labelling so people could choose. Eventually, after heavily contested votes in California and Washington the little state of Vermont (Bernie Sanders’ home state) passed a law saying GMOs needed to be labelled. Some food manufacturers complied. Then came the DARK Act. (Denial of Americans Right to Know). This was introduced in Congress to prescribe that any GMO information can be reached via the QR code on the packaging and shoppers could simply check the QR code to find out what GMOs were in their prospective purchase. Hmmm…so this is how that would work. Well, you scan the QR code and go the manufacturer’s website, where you are greeted with an array of products you might like to know about, then you choose the produce you are scanning and get to a list of ingredients and more advertising, then you can click on each ingredient to see which one is a GMO. Then, after about 10 hours of shopping, you have a basket full of food that is GMO free. Or you just buy organic.

The new law was signed into effect by Barack Obama who, as a presidential candidate, promised that he would bring forward GMO labelling. He has the support of 93% of American consumers, who a respected ABCNews poll recently showed want labelling.

Here in Britain and in Europe we take GMO labelling for granted. In the world’s beacon of freedom and democracy the will of 93% of can be blocked by the resistance of a handful of companies with political influence that dwarfs that of the citizenry. I wonder how the 93% of Americans who thought they were on the way to having GMO labelling, 20 years after we secured it in Europe, must feel now. Where there were referendums on GMO labelling, as in California, more than $30 million was spent with scare advertising to deter voters

Sugar - All They Want is the Tax, Man

Before everyone stampedes into a sugar tax, may I just try to shine a small beam of light of sanity into this increasingly hysterical ‘debate?’ I’m no sugar lover and have fought the good fight to keep my consumption as low as possible for many decades. In 1971, in my book About Macrobiotics I wrote: “If sugar were discovered yesterday it would be banned and possibly handed over to the Army for weapons research.’ But at the same time, without sugar we’d all be dead. It's all about how much we consume and in what form - simple or complex. But when even the Financial Times editorialises about ‘The Compelling Case for a Sugar Tax’ it’s time to dig a little deeper into the obesity and diabetes epidemic before rushing out to slap a tax on drinks containing sugar. What have taxes on booze, fags and petrol ever done to reduce consumption? Governments will always love the tax option, it’s so much easier to make money out of a problem than to solve it.

To begin with we need to understand about blood sugar. I am going to oversimplify. Life depends on glucose, the simplest sugar. When we eat or drink sugar, the glucose element quickly tops up our blood sugar level because blood sugar is glucose. The fructose element follows a different metabolic pathway and ends as fat or stored glycogen in the liver, which can then be converted into glucose when it is needed.

When we eat too much sugar the blood glucose level rises to dangerous levels and the pancreas pumps out insulin to bring it down. But it overshoots, so the insulin keeps taking glucose sugar out of the blood and before you know it, the blood glucose level is too low. The body panics as sugar is vital to cell function and brain function, so it tells the liver to release some of its stores of glucose, which helps. But the liver only has a limited supply and struggles to keep up with the demand, so the craving for sugar eventually becomes irresistible. It’s a natural inbuilt survival mechanism to crave sugar when blood sugar levels are low.

In our gut there are 10,000 different types of microbes, including useful candida yeasts, which help with the breakdown of sugar. When there’s a lot of sugar those candida multiply like crazy and outcompete the other gut flora. Worse than that, they mutate into a resilient and greedy fungal form that demands more and more sugar. Candida gets a lock on your brain and remotely controls your appetite to deliver more sugar. You can’t tax candida, you have to kill it. By starvation. Once candida is put back in its box the cravings for sugar diminish. Probiotics can help to suppress candida, as will berberine, grapefruit seed extract, garlic and oregano. But the key is to cut off its food supply. But starving candida ain't easy.

How does candida get such a grip? Candida’s takeover of our digestive process is much easier when the other gut flora, such as lactobacilli or bifidobacteria, are dead or dying.

This happens when you take antibiotics or regularly consume food that contains antibiotic residues, particularly non-organic chicken and pork. Other medications that kill off the digestive system microbial community and clear the path for yeasts and candida include birth control hormones, hormone replacement therapy, acid-suppressing drugs and steroids. Doctors who dish out antibiotics for common cold are helping drive the obesity epidemic. Maybe we should tax doctors who dish out antibiotics willy-nilly?

Caffeine plays a role, too. Ever notice how many people piously say ‘no’ to sugar in their tea or coffee, and then have a brownie or a big cookie? A brownie can contain twice the sugar of a can of Coke. Caffeine increases the flow of blood to the brain, where ¼ of our sugar consumption takes place – thinking is hard work and uses a lot of glucose. Drinking a double espresso accelerates your brain and the rate at which you burn glucose, leading to low blood sugar and sugar cravings. The liver just can’t keep up with converting glycogen to glucose. People ingest a lot more caffeine nowadays than ever before. In Britain there has been a dramatic fall in scone and teacake consumption too, with a corresponding rise in consumption of cookies, muffins and brownies. Drink it or eat it, sugar is sugar.

Alcohol also creates sugar cravings. Especially on an empty stomach. Alcohol increases insulin output, which reduces blood glucose levels and it inhibits the liver from producing glucose to top up those levels. Result? Uncontrollable urges to consume sugar.

How about a glass of milk? Milk contains 5% sugars, about half what you’d get from a can of Coke. Tax milk at half the rate of soft drinks? Tell that to the NFU. Is giving kids milk instead of water doing more harm because of the sugar than good because of the calcium?

If you’re going to tax sugar, then ALL sugar should be taxed, regardless of whether it’s in a brownie or a glass of apple juice or a cup of tea or a can of Coke. Whether sugar comes from a cane, a root, a bee, a cactus, a coconut tree, a maple tree, a cow, a goat, a camel or a grape or an orange or an apple or a pineapple it should be taxed equally. Otherwise you just move sugar consumption around based on pricing. Taxation never stopped people smoking but education and bans in public places has helped.

So what’s the answer? There are organic natural sweeteners such as stevia, licorice and erythritol that can provide a sweet taste without the glucose impact of sugar. But ultimately there are 3 words that sum it up: education, education, education. The Soil Association’s massively successful Food For Life school meals programme supplies 2 million school meals a day that commit to be freshly prepared, with local and organic ingredients. Jeannette Orrey, the legendary autobiographical author of “Dinner Lady” told me recently that Food For Life school meals now often have puddings made with half the sugar than usual and some participating schools are no longer serving pudding at all and the kids are cool about it. Time builds up bad habits. If kids grow up with minimal exposure to excesses of sugar, fruit juice, milk, cookies and other sugar sources and are helped to restore healthy probiotic conditions in their gut after exposure to antibiotics or other medications then they will be healthy adults with sensible appetites and a much lower predisposition to obesity and diabetes. For the rest of us, particularly those who have overdosed on sugar from an early age, the path to health is much harder and, for some, impossible. A tax will never solve this, education and behavior change will.

To create real change in the world sometimes you have to compromise

Last week four Soil Association trustees resigned from the charity accusing it of lacking conviction on organic. But to create real change you sometimes just have to compromise, says Craig Sams

In 1946 two pioneering women, Eve Balfour and Dr. Innes Pearce, founded the Soil Association. Eve was a farmer who developed organic principles by creating healthy soil on her farm in Essex. Dr. Innes Pearce ran the Peckham Project in one of London’s most deprived neighbourhoods and showed that good nutrition led to healthier families, better academic achievement by kids and fewer men deserting their wives. The Soil Association’s founding principle was that a healthy diet, supported by nutrient-rich organic food, would change the world for the better.

In 1966, the doctors, dentists, nutritionists and veterinarians who were members felt the Soil Association had become too farmer-oriented and resigned to set up the McCarrison Society, named after Sir Robert McCarrison, whose 1926 book on nutrition and health inspired both Balfour and Innes Pearce. This was a sad moment as it marked the divorce between the advocates of healthy soil and the advocates of healthy eating. A year later we founded our macrobiotic business Yin Yang Ltd (to become Harmony Foods and later Whole Earth) which brought together, at a commercial level, organic food and healthy eating.

Happily the Soil Association has rediscovered its roots. At a conference in 2002 titled ‘Education, Education, Education’ I gave the keynote speech that highlighted the few examples at the time of how better school food could improve kids’ behaviour and academic performance. Then the Soil Association, with Garden Organic, Focus on Food and the Health Education Trust got a £17 million Lottery grant to make it happen.

The grant money was well spent. Not only have over 4500 Schools enrolled with the project, and started to teach children to cook and grow and also taken them to visit farms, but the Soil Association Catering Mark has been developed too.This starts with the Bronze standard (75% freshly prepared, no GMOs, no hydrogenated fat, free range produce). Then they graduate to the Silver standard (a proportion of organic, a larger proportion of locally sourced, Fairtrade, MSC, LEAF). Then they go for Gold which takes it to even higher levels. The migration is only ever one way, from Bronze to Gold and the impact on organic suppliers is spectacular. The Gold holders are now asking the Soil Association for a Platinum category. More important is that schoolkids become aware of organic food, go home and challenge their parents. 950,000 school meals a day are served with the Catering Mark and it’s now also improving food served in nurseries, hospitals, care homes, offices and industrial canteens. By this time next year there will be 2 million school meals a day served to the Catering Mark standard – half of all schoolkids in the UK. This all sounds pretty good to me and if Dr Innes Pearce were alive she would be punching the air with triumphant joy that her dream back in the 1930s and 1940s was finally being realised. And this is just the beginning. The Catering Mark is the fastest-growing activity of Soil Association Certification and is sucking in more and more organic food as the biggest national foodservice companies get behind it.

“We compromised on organic, we compromised on sugar-like sweeteners, we compromised on restaurant food (where organic regulations don’t apply). We never compromised on GMOs. We are winning because we were pragmatic. And how we’re winning!”

But concern about the Catering Mark is the main reason why four trustees resigned from the Soil Association Council at the beginning of December. They felt it was an ethical sell-out to allow non-organic food in meals that bore Soil Association approval. They were unhappy that the standards permitted organic food that was frozen or canned, as this was not ‘fresh’ even if it was ‘freshly prepared’

I got into the world of organic food from the standpoint of the macrobiotic diet. We ate natural and wholegrain and organic whenever possible, which wasn’t often in 1967. But we mapped out a route that helped us get to where we are today. The reason the marvellous macrobiotic diet that has been the mainstay of my health and happiness for five decades never went mainstream was because it got hijacked by people who were rigid and restrictive. The macrobiotic guru and author of Zen Macrobiotics, Georges Ohsawa, was horrified to see this and just before he died he tried to correct this by writing that, thanks to macrobiotics he could enjoy whisky, chocolate and other taboo foods, as long as he did it in moderation. We compromised on organic, we compromised on sugar-like sweeteners, we compromised on restaurant food (where organic regulations don’t apply). We never compromised on GMOs. We are winning because we were pragmatic. And how we’re winning! The tide is turning. Finally clinicians are recognising that food is medicine and the Hospital Food Standards Committee have recommended Catering Mark as a scheme that can improve hospital food.

You might have missed it, but School Meals Week was in early November. The Minister of State for Education, David Laws MP, praised the Soil Association’s Food for Life Catering Mark, commending it as a scheme that allows school leaders to choose caterers who are committed to providing school children with high quality, nutritious food. He said: “My message is: ‘Quality really matters’. This is our challenge for 2015. I would like to see all schools and their caterers holding – or working hard towards – a quality award like the excellent Catering Mark.” The evidence is compelling – kids at Catering Mark schools have better attendance rates, better academic performance and better understanding of food and nutrition, the key to avoiding obesity.

The three journalists and a baker who resigned from the Soil Association cited the Catering Mark as the main example of how the Soil Association has lost its way. If that’s what losing its way looks like then perhaps the Soil Association should ‘lose its way’ more often.

Small is still beautiful

Who needs big organisations that are inherently inefficient in this age of smartphones and smart farmers? The future is small, the future is beautiful … and resilient

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society, in their wisdom, decided to bestow their Shackleton Medal (for Leadership and Citizenship) on me, and my wife Jo Fairley. The event was in Perth, traditionally known as the ‘Fair City’ but also a registered Fairtrade City. Supporters poured into the Perth Concert Hall and we met two schoolgirls whose school curriculum included writing an essay about Justino Peck, a personal friend of ours in Belize. Justino led the Toledo Cacao Growers Association in 1993 from near collapse to a vibrant cooperative built on supplying organic cacao to Green & Black’s for Maya Gold. Arguably he should have been awarded the Shackleton Medal – he moved heaven and earth to get organic cacao production up going in Belize.

What sank in as we prepared our speech was how much the world has changed. In 1993 British aid advisors and agricultural experts from the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations) urged the cocoa farmers to ignore us, warning that if they went organic and abandoned chemicals their cocoa orchards would be wiped out and they’d never be able to repay the money they’d borrowed to buy hybrid seeds and chemicals in the 1980s. Justino advised the farmers to trust us and go organic – most farmers don’t like spending money on chemicals anyway.

In the 1960s there had been a massive move towards big industrial scale cocoa plantations to ‘modernise’ cocoa production. 420,000 hectares of cacao were planted in Malaysia and over 200,000 in Bahia province of Brazil. Now there’s fewer than 20,000 hectares in Malaysia and even less than that in Bahia. What happened? Quite simply, the experts were wrong. They confidently gave crap advice that led to a huge waste of money. Big plantations planted cacao trees 8 feet apart with no shade trees (instead of 16 feet apart and with shade trees. Teams of workers were paid by the hour to harvest and ended up picking under-ripe pods to meet their targets. The result was cacao that was rubbish for anything but the cheapest chocolate. The Malaysians sent teams to Ghana to find out that complexity of flavour comes when you have lots of independent farmers growing cacao and picking it only when it’s ripe. In Brazil a disease called Witches Broom spread like wildfire in 1989, the fungicides failed to work and 90% of the trees in the Bahia region died. An awful lot of money, human effort and heartbreak went into this misguided scheme to ‘modernise’ cocoa farming. A lot of women got cancer or had deformed births from spraying chemicals into the underside of the trees. Some plantations wouldn’t give women jobs as backpack sprayers unless they could prove they’d been sterilised. Cheap food at what cost?

Now it’s all changed and all the chocolate companies are actively courting smallholder producers. Big is not beautiful, it’s a disaster. Tyre companies like Michelin want smallholders to plant rubber trees. Unilever want them to plant oil palm. The big plantations don’t work. Now everyone has to make nice to the smallholders. They have the whip hand and, organised into cooperatives, can command fair prices, supported by the Fairtrade Mark and other assurances.

The thinking behind depopulating the countryside was that all those peasants were needed to go and work in factory jobs, assembling computers and cars. Only robots now do the job cheaper. Apple’s new factory in Arizona will make computers in the USA again, but with very few jobs. But there’s no point in making stuff if nobody has the money to buy it. The independent smallholder farmers, getting fair prices for what they produce, will be an important market for manufactured goods.

What’s more, independent people who own their own business or land are the backbone of any representative democracy. They’re harder to push around.

Just look at what a mess ‘Big’ has got us in. Big farmers in the US and EU depend on subsidies for half their income – they’d go bust overnight without £400 billion each year of taxpayer support. Big supermarkets are struggling, squeezing suppliers for cash to prop up their flagging share price, while independent butchers, bakers and brewers and other small retailers are popping up all over the place.

“Just look at what a mess ‘Big’ has got us in. Big farmers in the US and EU depend on subsidies for half their income – they’d go bust overnight without £400 billion each year of taxpayer support. Big supermarkets are struggling, squeezing suppliers for cash to prop up their flagging share price”

EF Shumacher wrote Small is Beautiful – as if People Mattered and went on to be president of the Soil Association. Who needs big organisations that are inherently inefficient in this age of smartphones and smart farmers? The future is small, the future is beautiful…and resilient. Just look at the cacao example – it’s the same wherever you look.

Was Adam a Fungus?

At the Soil Association conference in October I heard comments that the name wasn't very sexy and maybe something like 'The Organic Society' might be more compelling. I have to disagree, based on my, admittedly quirky, interpretation of world history. Also, I'm an acolyte of the Zen macrobiotic guru, Georges Ohsawa, who said that humans and soil are a unity. Here's my take on what he meant.

When life began on earth 500 million years or so ago there wasn't much around beside stringy little mycorrhizal fungi living on rocks. A mycorrhizal fungus had to erode a piece of rock with enzymes, helped along by carbonic acid from rain (the air was mostly carbon dioxide back then). It would get enough carbon to survive.

Then a miracle happened - little green bacteria called cyanobacteria managed to harness sunlight in order to turn carbon dioxide and water into a simple carbohydrate, glucose sugar inventing photosynthesis. That was when life really kicked off. The mycorrhizal fungi, no slackers, saw the opportunity and created chain gangs of these sugar-producing bacteria, sucking out some of their sugar and feeding them with minerals like phosphorus that they harvested from rocks. The chain gangs got bigger and bigger, organised into fan shapes to maximise capture of carbon dioxide. Then they installed tubes that helped deliver the sugar that much quicker to the ever hungry, sugar-addicted fungi down below.

These were the earliest plants. Nothing has changed since. Even a mighty oak tree

is nothing but a collection of tubes that carry water and minerals up to the sugar factories in the leaves and carry sugar down to the hungry mycorrhizae clustered all around the roots. Then they form a network of filaments that can be 8 miles of superfine threads in just one cubic inch of soil. They communicate with each other through chemical signalling, electric pulses, smell and touch, making sure that the system runs smoothly.

So far so good, but what about all the other organisms down there? We know of 10,000 different bacteria and fungi that all have some role. They need sugar too. And the only way they can get it is to make nice with the mycorrhizae, the sugar barons of the underground. So they do. They even copy fungi in shape, so much so that before electron microscopes people thought bacteria like actinomycetes and streptomyces were fungi because they formed the same stringy filaments as their sugar-dealing masters. We all mimic our wealthy betters, so why not bacteria? Those filaments help to channel mineral nutrients to the fungi that reward them with sugar before trading it on to the plant up above. If mycorrhizae are Mr. Big then the actinomycetes are the street dealers in the sugar racket.

It's not all peace and love, though. From time to time nasty fungi and bacteria that eat plants' living tissue come along. The mycorrhizae have the answer, though. They just feed sugar to SAS commando bacteria, which quickly mulitply and kill off the invaders. You might call them an immune defense system. Most of our antibiotics come from soil bacteria - they're very, very effective at wiping out nasty bugs. Once the killer bacteria have seen off the invasion, the sugar supply tapers off and their population is reduced to a minimal state until they're needed again.

Inevitably, some rebel fungi and bacteria thought 'Why are we so dependent on the mycorrhizae? Let's get mobile, grow legs and wings and mouths and eat the plants instead of waiting passively to be fed" Animal life emerged, all the way up to us humans. We all have our own resident population of bacteria and fungi that date back to the origins of animal life. They are our immune system, just as mycorrhizae are the plant's immune system. They may be little, but there are 500 to 1000 bacterial species in a human gut with 100 times more genes than the human genome and comprise 10 times the total number of human body cells. Humbling, isn't it? Are we just walking food gathering mechanisms for a bunch of clever bugs who have been evolving for half a billion years before the first humans came along.

Are we a triumph of their evolution?

And did the name 'Soil Association' unconsciously (or bug-consciously) reflect the fact that it is an organisation dedicated to restoring the chemical-depleted global population of soil-dwelling organisms to their former glory?

Sharing Economy

I farm 20 acres, mostly woodland and orchard, with 2 acres of organic vegetable production. I farm people – and they farm me. They work the vegetable land and they call themselves Stonelynk Community Growers.

20 members put £50 a year into the kitty. I match fund it and pay for the Soil Association certification. Then we split the crop 50-50. I sell my half to local natural food stores, box schemes and restaurants, they eat their half. They get £500 worth of fresh vegetables and work 100 hours a year. The farmer next door does any machinery work, like rotovating. This is just one example of how the sharing movement is gaining traction.

I was keynote speaker at the ‘Grow It Yourself’ launch in Birmingham in July. It’s an event that Mark Diacono of Otter Cottage described as a ‘Gardeners’ Glastonbury.’ Allotmenteers, community gardeners, gardening journalists and publishers were all there. People who grow their own food together have a special bond. Most grow organically – who would spray insecticide on a lettuce they were going to serve a day later to their friends and family?

When people grow and share their produce their attitude to food changes. They want provenance and trust. They buy local. They insist on organic.