80 years of ‘Organic’ food and farming

While since earliest times farmers have understood the importance of giving back to the land in return for the food that it provides us, the word ‘organic’ to describe this way of farming was first used by Lord Northbourne in his book ‘Look to the Land’ published in 1940. It came out at a time when industrial farming had relentlessly destroyed the accumulated fertility of millennia and sparked a debate for sustainable farming that continues to this day. But where did the inspiration come for Northbourne’s ideas? The trail leads back to the late 18th C and to the ideas of the poet and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose 1790 book, An Attempt to Interpret the Metamorphosis of Plants, laid the foundations for modern plant biology.

Two hundred years ago Goethe propounded the idea that there was a life force in plants. He saw that plants were driven by an ongoing intensification and that a ‘cycle of expansions and contractions’ shaped the plant, making either leaf, flower or seed depending on the degree of the ‘dynamic and creative interplay of opposites’. This is what underpins the harmony of the universe and the harmony of life on earth down to the tiniest life forms.

Rudolf Steiner wrote extensively on Goethe and developed Anthroposophy on the foundation of what he called Goethe’s ‘spiritual-scientific basis’ of thinking.

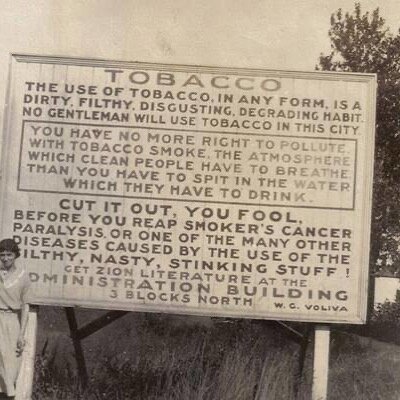

Goethe’s doctor was Christoph Hufeland, author of Makrobiotik oder Die Kunst, das menschliche Leben zu verlängern (1796), (Macrobiotics: the Art of Living Long). He was a naturopath who was also doctor to the King of Prussia Frederick Wilhelm lll, Schiller and Goethe, all part of the Weimar set. His ideas on human health and vitality mirrored Goethe’s observations on plant health and vitality and he was a close friend of Samuel Hahnemann, creator of homeopathy. Goethe hosted a Freitagsgesellschaft (‘Friday Society’) at which Hufeland would read from his drafts of Makrobiotik. Hufeland’s medicine envisaged a life force that should be nourished - the Hufelandist movement was largely vegetarian and inspired the Lebensreform (“Life Reform”) movement in the rest of Germany over the next century.

Steiner was an active proponent of this Lebensreform movement which sought a ‘back to nature’ way of living, with an emphasis on healthy diet and alternative medicine. In 1924 Steiner gave an agriculture course that was organised by biodynamic farming researcher Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. Pfeiffer then went on to found the 800-acre biodynamic research farm at Loverendale In the Netherlands that provided the practical proof of Steiner’s theory. So in 1939 when Lord Northbourne decided to set up Britain’s first biodynamics conference he invited Pfeiffer to run it. The resulting Betteshanger Summer School and Conference brought together a wide range of proponents of biodynamic farming. It was a seminal event in the history of the organic farming movement. A few months later Germany invaded Poland, World War ll broke out, making further collaboration difficult. A year later, in 1940, inspired by the visionary 9 days of the Betteshanger Summer School, Lord Northbourne’s book ‘Look to the Land’ was published.

It was a best seller. In it Northbourne identifies debt and ‘exhaustive’ farming as having the potential to lead to ‘the extermination of much of the earth’s population by war or pestilence.’ He points out that if the land is sick, then farming is sick and that people will be sick. That Nature ‘is imbued above all with the power of love; by love she can after all be conquered but in no other way.” In ‘Look to the Land’ Northbourne coins the term ‘organic’ to describe farming that sees the farm as an organism. “The mechanism of life is a continuous flow of matter through the architectural forms we know as organisms. The form alone has any life or any organic identity.” In this he mirrors Goethe’s writing on botany.

He wrote that to quarrel with nature makes no more sense than a ‘quarrel between a man’s head and his feet.’ He described ‘organic’ farming as “having a complex but necessary interrelationship of parts, similar to that in living things”. Although nobody had previously used the word ‘organic’ to describe this way of farming, ‘Organic’ became, in English, the accepted descriptor.

In 1943 Eve Balfour’s ‘The Living Soil’ began by quoting across several pages in her first chapter directly from ‘Look to the Land’ She founded the Soil Association 3 years later in 1946, with support from Northbourne. Her book and Northbourne’s informed the debate about the future of farming in Britain, a debate that was closed off by the Agriculture Act of 1947 where ‘exhaustive’ agriculture to maximise production prevailed. Subsidies were given to farmers who used ICI’s chemical fertilisers and farmers who refused to ‘modernise’ were threatened with land confiscation. Farming was nationalised and the organic movement was marginalised.

In Japan, Sagen Ishizuka, doctor to the Japanese imperial family, followed up on Hufeland’s macrobiotic ideas and developed “shokuiku” (“Food Study”) and in 1907 created the Shokuyo (Food for Health) movement. A shokuiku follower, George Ohsawa, subsequently published a book in 1960 setting out the principles of healthy living and called it ‘Zen Macrobiotics’.

Ohsawa knew of Christophe Hufeland and freely adopted Hufeland’s term ‘Macrobiotik’ to describe his diet based on similar principles, embodying a yin and yang approach to food. He sought out and met a descendant of Hufeland in 1958. Ohsawa’s seminal book was adopted by the emerging alternative society and inspired the natural foods movement of the 1960s that supported whole food and organic farming. The natural foods stores adhered to macrobiotic principles, selling only whole grains, eschewing sugar and artificial ingredients and supporting organic food.

So it was that Goethe’s doctor Christophe Hufeland coined the term “Makrobiotik” that drove the Lebensreform movement and inspired Rudolf Steiner to develop the anthroposophical farming principles known as ‘biodynamic, which were proven in practice by Steiner’s follower Pfeiffer. Lord Northbourne’s book gave the movement momentum and the name ‘organic.’ A Zen version of the same principles emerged in the 1960s and helped drive the natural and organic transformation of farming, diet and medicine that will ultimately restore our soils and thereby underpin the health and vitality of us all.

"Who knows himself and others well / No longer may ignore: / Orient and Occident dwell / Separately no more” Goethe