This paper outlines the global threat from Climate Change and proposes a simple economic model as a practical solution through which land use innovation can drive behaviour change and reverse global warming. The planet is warming, we are losing the race to save all the inestimable physical wealth and cultural value that humankind created over the centuries and yet we have singularly failed to use the most efficient tool for reducing carbon dioxide levels: photosynthesis. Nothing else comes close to sucking carbon out of the atmosphere, yet we neglect it.Two decades of policies to address the rising threat of catastrophic climate change have focused on reducing emissions. They failed, however, to slow the increase in greenhouse gas levels. Instead, directly and by default, government policies have brought about continuing increases instead.

Forestry and farming are the cheapest and most effective ways to take carbon out of the atmosphere, sequestering it in the vast unexploited reservoir of the soil and trees. Yet instead of actively pursuing these low-cost options we have deforested and degraded forest carbon and soil sinks. How can we fix this?

The “4 per 1000” (‘Quatre pour Mille’) initiative launched at the Paris COP21 aims to do just that, by rewarding carbon farming.vBritain is a signatory and a Forum and Consortium member. “4 per 1000” states that, if farming and forestry increased soil organic carbon annually by four parts per thousand per year, that would be enough to totally offset the annual 16 billion tonnes increase in greenhouse gas levels. With carbon a marketable crop, we could stop worrying about global warming.

In 2015, the French National Assembly responded to ‘4 per 1000’ by setting a €56 (£50) a tonne carbon tax to comes into effect in 2020.

Carbon emissions reduction policies have failed so far:

HM Govt has spent over £1.5 billion supporting Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), the idea that you can capture CO2 emissions and bury them securely in the ground. For CCS to work and be effective it would cost at least €70 per tonne CO2 stored and require an increase in fossil fuel use of 35%.

The voluntary market has created credits for 1 billion tonnes of CO2 in the past 10 years. That’s a mere 1/500 of emissions. Cap and trade is subject to political vagaries. The European Climate Exchange and the Chicago Climate Exchange went bust in 2010 when EU political decisions led to a gross oversupply of carbon allowances.

The EU Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation requires mixing sugar beet ethanol, rapeseed oil or palm oil with petrol or diesel. 7 million tonnes of the world’s annual palm oil production of 66 million tonnes is burned as biodiesel, much more than is consumed as food in the EU. Land across the EU is degraded by intensive production of sugar beet and rapeseed for biofuel use, with negligible reductions and, even in some cases, increases in CO2.

The “4 per 1000” initiative is predicated on there being a price on carbon, whether emitted into the atmosphere or removed from the atmosphere. The Government sets a price for carbon and all emissions of CO2 are paid as part of a company’s tax bill, declared as part of its annual returns. If a company can purchase carbon offsets for less it can deduct these offsets from its tax bill from carbon aware farmers.

What would happen if there were a £50 per tonne CO2 price?

Nitrates, pesticides and herbicides would become uneconomic in many applications and farmers would minimise or abandon these inputs

Farmers would increase soil carbon by the use of grass leys and compost. They would minimise tillage and grow green manures to keep ground cover all year round

Carbon from straw, sawmill waste and forestry arisings would be converted into biochar (agricultural charcoal) then added to the soil to permanently enhance fertility and increase the carbon in the soil ‘carbon bank.’ Biochar is 80-90% pure carbon and stays in the soil for centuries.

Farmers would plant trees and hedgerows instead of growing rapeseed for biodiesel.

Wood burning would 10.5 billion be disincentivised. Wood would replace steel and concrete in buildings and homes. Wood is carbon negative. Modern cross lamination technology produces wood that equals or exceeds the strength, durability and load bearing capacity of concrete and steel.

The £1.5 billion Government subsidy to date wasted on carbon capture and storage research would be saved.

Peat use would end overnight - peat bogs capture more carbon than any land use other than salt marshes.

The sea would be more productive. Reduced fertiliser use and reversal of soil erosion would herald the end of harmful algal blooms that damage coastal ecosystems and fish stock populations.

Soil is the world’s most important and valuable commodity. With a realistic carbon price, we would not suffer the resource misallocation of agricultural subsidies such as in the Common Agricultural Policy.

Wind and solar are getting cheaper, but are nowhere near as competitive as 4/1000. Money has been poured into supporting wind energy. Every tonne of CO2 saved by onshore wind costs €162, from offshore wind £267.

A regenerating degraded forest can profitably generate CO2 savings for a cost of less than £5 tonne CO2. Forestry management costs of planting, then thinning are minimal. Forests, pasture and arable farmland can easily sequester “4 per 1000 per annum.” Yet we still lose 31 football fields per minute globally of productive agricultural land because industrial farming methods need take no account of carbon emissions.

How does a Carbon Price affect Fossil Fuel Prices?

A carbon tax would add $10 to a barrel of oil. That is well within the range of fluctuations in the oil price (e.g. recent OPEC decisions).

There is a financial opportunity. The Government simply establishes a tax that can be offset by carbon credits. This then puts carbon dioxide, like any other valuable commodity, in the hands of markets.

Fossil fuel emissions are 33 billion tonnes CO2 a year globally. At £50/tonne the market for carbon credits would be more than £1.5 trillion. If Britain leads on this by example then London would be the financial hub for carbon trading . The City of London has the depth of liquidity and the reputation for integrity that a global carbon market will need to succeed.

The flow of cash into sequestration will be transformative. Agricultural subsidies can fall away without impacting on land values. Rural economies will be invigorated and farming can begin to remediate the misallocation of resources that current CAP policy encourages.

Auditing, validation and certification of carbon sequestration represents an opportunity for the certification industry, much of which operates out of the UK.

What is the scale of the opportunity? Carbon sinks are primarily forests, fields and meadows.

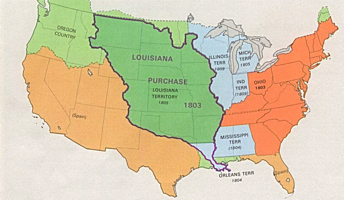

The world has 1.5 billion hectares of arable land, 4 billion hectares of forest and woodland and 5 billion hectares of grassland, a total of 10.5 billion hectares that can be put to work removing CO2 from the atmosphere. The annual net increase in CO2 levels is 16 billion tonnes. If every hectare of our available land annually removed 4 tonnes CO2 then we would remove 41 tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere every year, which would get us back to pre-industrial levels in just 35 years.

Is 4 tonnes CO2 per hectare realistic?

La Vialla, a biodynamic family farm in Tuscany, comprises 1440 hectares including arable, pasture, woodland, vines and olives. Taking this as an example and microcosm of the global distribution of land use types, the University of Sienna, using IPCC methodology has evaluated La Vialla’s annual carbon cycle for the past eight years. Calculations show that 4.24 tonnes of CO2e per hectare have been captured every year for the past eight years.

An obvious criticism of soil and forest sequestration is that it can be reversed through human and natural impacts. A farmer can plough up the soil, a forester can chop down the trees and then much of the carbon captured is released back into the atmosphere. An additional risk is that fire, war, flood or hurricane can reduce the carbon store.

A two-part payment can address this by providing:

a payment for the annual increment of CO2;

an additional ‘interest’ payment on the carbon that is stored in the carbon ‘bank.’

Soil is the foundation of our natural capital. In a capitalist system it should be valued.

Farmers can insure against loss of carbon. Banks will advance loans against land to farmers who operate best practice carbon farming in the knowledge that the asset that is loaned against is increasing in value as its carbon content increases.

The cost of low carbon food would come down and the cost of high carbon food would go up. No longer would price be a barrier to eating food that is rich in nutrients, low in pesticide residues and which delivers tangential social and environmental benefits.

Carbon sequestration in farmland, pasture and forests is a cheap and effective way of reducing greenhouse gas levels. Compliance with agreed Paris COP 21 targets will be unlikely if we continue to depend on technological solutions and biofuels to reduce emissions. Using up precious soil and forests for the production of biofuels is wasteful, uneconomic and does nothing to help mitigate climate change. An economic incentive to maximise soil and forest sequestration of carbon dioxide is the most effective, practical and low- cost solution to achieving greenhouse gas reduction.