This was my keynote speech at the launch of Slow Food UK back in 2005. I was the Chairman of the Soil Association at that time (and went on to be Chair of Slow Food UK)

The Soil Association was founded in 1946 with a mission to research and develop an understanding of the link between the health of the soil and the health of the plants, animals and humans that it supports and to then establish an informed body of public opinion on these matters. That informed body of public opinion was established but still had no political impact so we went one step further and helped create a $30 billion worldwide market for organic food. Dr Innes Pearce, one of our founders, had shown, with the Peckham project, that if working class people were educated in how to freshly prepare wholesome food the indicators of social well being such as education, income, marital stability and staying out of jail all improved. So we married agriculture with social and health issues. How, you may ask, does this fit with the Slow Food philosophy, which has its roots in gastronomy and food culture?

Last year the Nobel Prize in medicine went to Richard Axel and Linda Buck, who mapped the code between genes and odour receptors. They found that we have 350 genes that connect to our smell receptors. There are another 600 genes that are dormant, reflecting humanity’s reduced reliance on smell. Taste uses only 29 genes, and sight a mere 3, so this research emphasises the importance of our sense of smell. As the Italian novelist Italo Calvino wrote: “Everything is first perceived by the nose, everything is within the nose, the whole world is the nose.”

So how is it that smell, or flavour, is so important? When plants evolved on this planet, long before animal life, they needed to create substances to protect themselves against oxidation from oxygen, ultraviolet light from the sun and the various viruses, bacteria, fungi, and insects that threatened their existence. These antioxidants, anthyocyanins, antiseptics and antifeedants come under the general name of flavonoids. When animal life evolved it never created any of these substances, Nature is too efficient for that. Instead we animals get them from our food. How do we know where they are? By our sense of smell – what we perceive as flavour is actually the antioxidants and other health-giving flavonoids that are in food. So when food tastes really good to us it is because it really is good for us. Cuisine and digestion concentrate and combine these flavonoids in a way that underpins our health and is at the root of our culture and civilisation.

When a farmer uses artificial fertilisers, pesticides or other crop protection chemicals the plants produced have reduced levels of these flavonoids as they don’t need to produce them. Organic crops have to protect themselves with their own natural defensive chemicals, so their levels are often 50% higher. These natural defensive chemicals taste good to us for evolutionary reasons. That’s why organic food tastes better and is better for us. Gastronomy and good health spring from the same source, healthy soil and healthy plants.

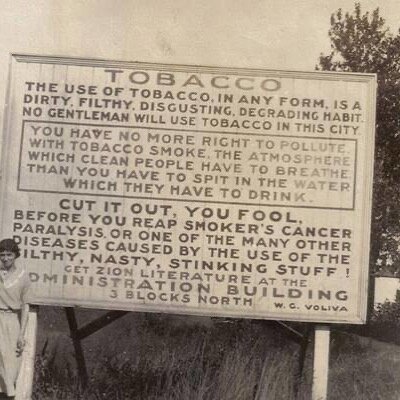

The use of chemicals and artificial fertilisers springs from and underpins the industrialisation of agriculture – they reflect the need to reduce labour costs and to squeeze every last drop of cash out of every hectare of land. The use of artificial colourings and flavourings in food processing deceives our noses into thinking we are eating good food when we aren’t. That’s why organic farming and food processing regulations exclude these unnatural chemicals.

Organic farming is by nature human scale and mixed. Smaller farms are actually more efficient and more productive than large farms and, as the oil price rises, industrial agriculture will need ever increasing subsidy support. The Soil Association supports the restructuring of land use around optimal sized mixed farming units. Many of the pictures you saw this morning were from Soil Association conferences where Pam Rodway organised superb Slow Food lunches drawn from local producers, some organic, some not.

We heard this morning about proposed guidelines for Slow Food. In the early days of organic food a lot of people jumped on the bandwagon and we soon saw the need for standards defining the word ‘organic.’ This led to the need for inspection protocols and then to certification systems. The Soil Association pioneered these developments and has since helped the Biodynamic Agriculture Association, the Henry Doubleday Research Association, the Marine Stewardship Council, the Vegan Organic Trust, the Forestry Stewardship Commission and the Fairtrade Foundation to create efficient effective systems to ensure that claims can be verified. The day may come when Slow Food will want to protect its integrity and I hope that we will be able to help by sharing our experience and expertise in this area.

We are only too aware that inspection and certification is a burden on the small producer – I myself pay far too much in fees for a bureaucratic process that is excessive relative to my tiny levels of production. The Soil Association is developing and testing systems that will enable a high degree of self-certification and a reduced frequency of inspections, so that the cost of being certified organic for the small producer can be dramatically reduced. However, these need to be approved at a European level, which will take a long time. An ideal outcome might be that Slow Food certification enabled small producers to have an independent assurance of their integrity and that we could help with this.

Allow me to read from The Little Food Book by, ahem, Craig Sams. “Slow Food sees children as the Slow Foodies of the future and seeks to educate them in the taste of food and in how it is produced. They even produce a book teaching kids about flavour and its appreciation via ‘aware’ tasting.”

Our Food For Life campaign to improve school dinners inspired Jamie Oliver’s influential TV series. The Dinner Lady and author Jeanette Orrey, who now works for the Soil Association, is now running a cooking school for dinner ladies at Ashlyns Farm in Essex. Our Policy Director sits on the Government committee to improve school meals. Palates that are trained in childhood never lose their taste for good food. Our inspiration for this campaign came from the example of Italian schools, where Slow Food has been so instrumental in bringing about change. A few weeks ago Jo and I spoke at a meeting at Sacred Heart school in Hastings where the headmistress is determined to produce school dinners on site when her catering contract expires in a year’s time.

In all our work, the Soil Association sees itself more as an enzyme to bring about change rather than as an empire-builder. We initiate and support change without trying to control it.

Let me describe one effort, typical of what is beginning to happen all over the country at the local level.

Jo and I have recently taken over our founded-in-1826 local bakery in Hastings and expanded it to a retail shop that sells organic local fruit and vegetables grown locally. Last month we budgrafted 25 trees of the near-extinct Saltcote Pippins, one of the surprisingly few indigenous varieties of apple that Sussex can boast, which originated 5 miles from Hastings in the early 19th Century. Eventually we’ll harvest them from our orchard in November for sale when they reach their prime in late January and February and use them in our apple turnovers. We have lamb and beef from the salt marsh a few miles away at Pett Levels. We sell cheeses from sheep’s milk that is the natural dairy product of the Downs to the north and south of us and cheeses, ciders and wines that represent the continuation or the revival of the traditional foods of East Sussex.

We’ve kept on baking Judges’ popular and traditional white bloomers, teacakes, Eccles cakes, wet nellies, pasties and sausage rolls – but now all 100% organic. Many customers have commented on the improvement in flavour, but we have not blown the organic trumpet at all. We’ve introduced almond croissants, sweet little gingerbread seagulls, sourdough rye, onion focaccia and pan Pugliese. Whenever you go into the shop there is something to be sampled – the sale of local cheeses has soared.

ALL our breads, even our standard white tins, are Slow Bread – which to us means that the doughs ferment at least 18 hours and that the starters are nourished and built up for 3 days before the bread goes into the oven. Some people with bread allergy have found that they can eat it without ill effects.

We aim to be part of a Slow Food ‘convivium’ that will reach out to local producers and bring together local customers who share the Slow Food ideal. Now that we’re up and running we plan to have regular Slow Food lunches where our customers will sample the produce of East Sussex producers and become part of a network that combines enjoyment with reduced food miles, just-picked freshness and that ineffable satisfaction that comes from being part of a community. When your database of membership for the UK is up and running, remember that there are 60,000 members of the Soil Association and HDRA as well as perhaps another 100,000 supporters who are prospective members of local conviviums.

The Slow Food Manifesto speaks of ‘dealing with the problems of the environment and world hunger without renouncing the right to pleasure.’

Organic farming offers solutions to the problems of the environment. Decentralised self-sufficient farms are the answer to world hunger. Organic production fulfils the aspirations of gastronomy to take pleasure in the production, preparation and shared enjoyment of good food. With these goals in common, I see Organic and Slow Food as natural allies – with a shared interest in combining the joy of eating with responsibility for health and the future of the planet.