Apart from Wagner, of all the music that has embedded itself in my mind and my soul, perhaps none had a deeper grip than that of Mose Allison. Born on a cotton farm in northwest Mississippi in 1927, he was a country boy who experienced and was shaped by the Depression years in the Midwest. Perhaps he resonated with me so much because our farm was a few hundred miles north in Nebraska. Whatever, he got me deep down. Country boy with jazz infusion.

I was 16 when I first heard Mose’s music in 1961, on the school bus on the way to Bushy Park School, the first dedicated American high school in London. On the 45-minute bus ride from our pickup point in Ealing, as I'd be trying to remember a few more lines of a Shakespearean sonnet or finish other homework, Cam and Tom, two fellow students, would be harmonizing on "Young Man" or "Parchman Farm." Cam and Tom both went on to study at Ealing Technical College - I went off to the University of Pennsylvania, but came back to London from Philadelphia every summer vacation. We’d all hang out with the Ealing crowd, including Pete Townshend (the Who) and Michael English, an artist best known for his posters for the UFO Club as Hapshash and the Coloured Coat. We'd go to the Flamingo Club in Wardour Street in Soho for the all-nighter sessions where Georgie Fame sang his rocking version of Parchman Farm and other Mose favorites.

Cam's girlfriend Marika also studied at Ealing and they invited me to join them in Formentera, then a sleepy little island south of Ibiza, where we stayed in a pension called the Fonda Pepe. My accommodation was a converted pig sty on the nearby road. We’d hang out on the Mitjorn beach during the day and at La Tortuga, a nearby bar run by an American called Don, in the evening. Don had all the Mose Allison albums up to that time and the bar resonated with his music and various jazz records. Walking back along Formentera’s dusty rocky roads at night I’d be singing ‘Young Man’ or ‘Parchman Farm’ to any hoopoes or mosquitoes that might be listening. Cam left the island and a day later Marika and I began a multi-year relationship. She was a Mose fan too, so our good times together were often accompanied by him on the turntable.

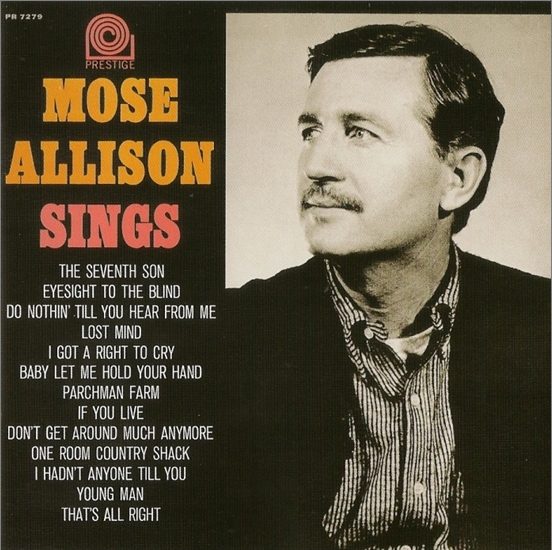

In February 1965 I headed east to India. I had purchased a small battery-powered turntable and carried with me 4 albums: Kirk’s Work, Georgie Fame Live at the Flamingo, an Egyptian dance music album and Mose Allison Sings. Music is the international language and having this music with me in by dad’s old Marine Corps duffel bag (I wore his combat jacket as well) helped to make friends wherever I went. But I was alone a lot, too. Mose kept me company and I learned the songs on that album by heart. One Room Country Shack was the song that was most compelling at that time. It describes being ‘1000 miles from nowhere’ and ‘my only worldly possession is a raggedy old eleven foot cotton sack.’ As I sat alone with my duffel bag in a shelter on the road from Abargoo to Yazd in the lunar landscape of southern Iran I shared the feeling in Mose’s plaintive wail.

In Philly I’d catch Mose at The Showboat whenever he came to town, at least once a year. It was always a bit disconcerting to hear him moaning and grunting when he played. That never ended up, thankfully, on his recordings. Thelonius Monk did the same thing when I saw him at the Five Spot, I guess some pianists need to growl the notes as they play them, maybe using their voice to stay in key.

The lyrics of Young Man are even more appropriate these days: “Nowadays, the old men got all the money, and a young man ain’t nothing in the world these days.” Mose nailed it then and all his later music did it too. ‘Middle Class White Boy’ was his sardonic take on the hippie scene. It kindly captured that moment of change in popular culture.

I saw him many years later at Ronnie Scott’s and we had a chat about the Philly scene. By then the Showboat had closed. Mose lamented the fact that a great club had shut down because the economics of a jazz club no longer worked. Hearing him at Ronnie Scott’s, with a quiet and respectful audience, was quite different to the raucous atmosphere of Philadelphia jazz clubs, where even John Coltrane had to blow extra loud to drown out the chatter.

I suppose my favourite line of all from Mose’s great repertoire of one-liners was ‘Your mind is on vacation but your mouth is working overtime.’ A lesson that I am still trying to learn many decades after I first heard it.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCpekvOkwNM&w=560&h=315]