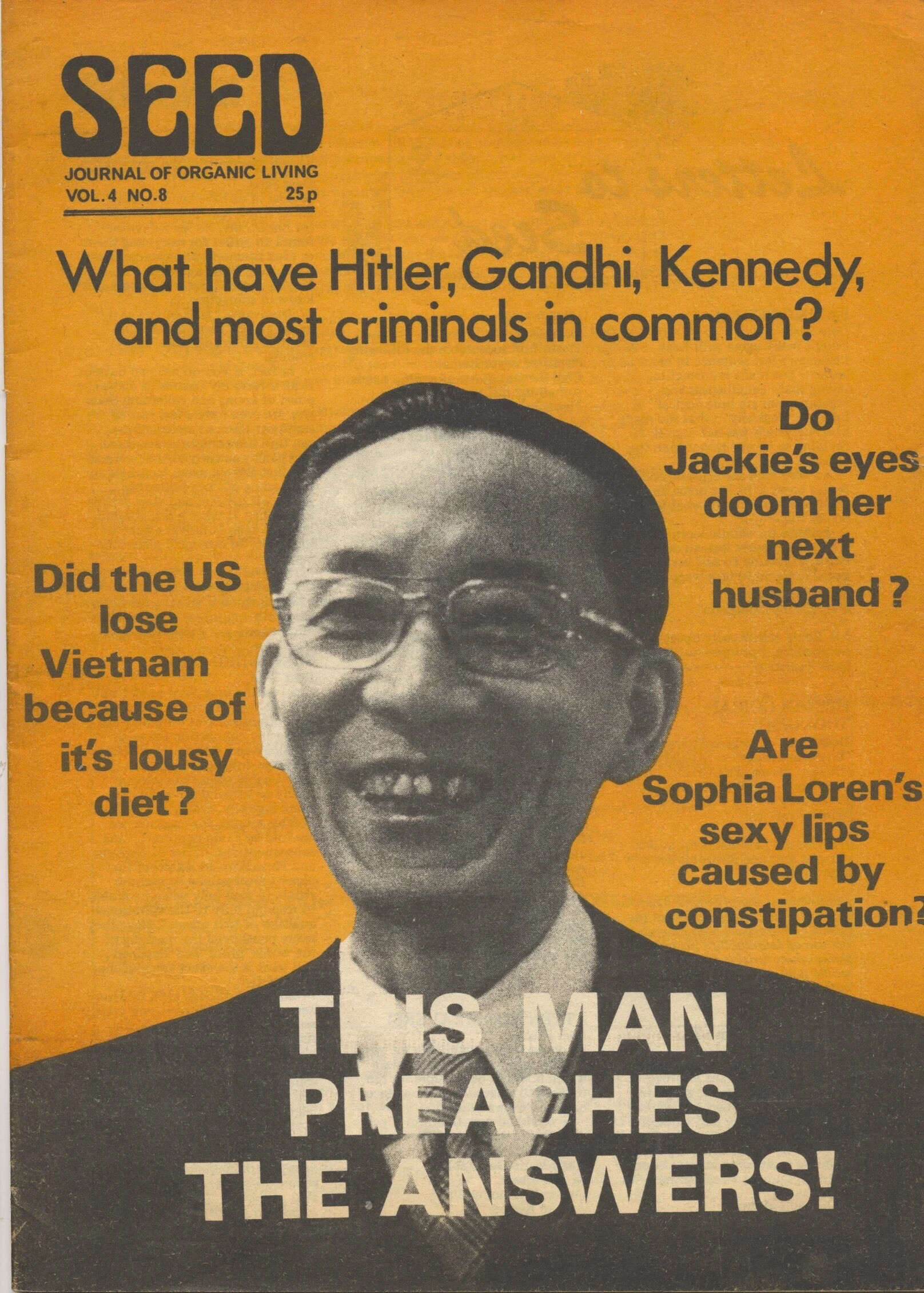

Modern Zen macrobiotics was created by the Japanese leader George Ohsawa. His leading apostle was Michio Kushi. Kushi died in December, leaving the macrobiotic movement leaderless for the first time in its history in the West. In any belief system there is always the potential to confuse the messenger with the message. The Ten Commandments ban worshipping graven images and Islam prohibits images of Mohammed. This prevents believers worshipping a fellow human who connected with the universal spirit of love and peace (or ‘health and happiness’ if you prefer) instead of seeking that connection themselves. In macrobiotics the tendency to follow the man rather than the practice has been a marginalising factor that has kept it as a cult instead of the universally popular diet that we once thought it would become. Yet macrobiotic principles are now the guiding principles of the renaissance in nutritional awareness that is gathering pace worldwide. It looks like we’ve won, just not under our flag.

The Zen Macrobiotic diet originated as a reaction to the introduction of American food in Japan. In 1907 The Shoku-Yo-Kai association was formed to educate the public in healthy eating and to encourage a return to the traditional Japanese diet and avoid the meat, dairy products and sugary refined foods introduced from the West. Japanese were beginning to succumb to hitherto unknown diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer. The President of Shoku-Yo-Kai was George Ohsawa in the 1930s. He was jailed and nearly executed because he opposed Japan’s militaristic and imperialistic adventures that led to World War 2. One of his students was Michio Kushi, who took the message to the US in 1949. He was not the only one. Another was a Hollywood-based Shoku-Yo-Kai practitioner called Dr Nakadadi, who in 1947 cured my father Ken, who suffered debilitating intestinal disease for years after fighting as a Marine in the Pacific war. But it was in the 1960s that Ohsawa’s book Zen Macrobiotics lit the fuse under the macrobiotic rocket. It married the Taoist philosophy of Yin and Yang to diet and lifestyle. Taoism, like Zen, ideally seeks to achieve states where you transcend earthly day-to-day worries and become a mover and shaker while playing and staying in a state of constant bliss. This is why macrobiotics appealed so much to the Sixties hippie generation, who experienced those states temporarily and sought something that could bring them there without having to rely on psychoactive substances.

Ohsawa died suddenly in 1966, leaving the macrobiotic movement leaderless.

Michio Kushi on the East Coast and Herman Aihara on the West Coast, took up Ohsawa’s mantle. Kushi set up the East West Institute in Boston. It was a mecca for burned-out hippies who would make the hajj to Boston and work in the study centre or the associated restaurant and food wholesaling business Erewhon, while learning the philosophy and how to cook the food. Kushi’s lectures to his followers were published in The East West Journal and the Order of the Universe magazines, reaching more than 100,000 subscribers worldwide. His students became the missionaries of macrobiotics beyond Boston. Many of them came to London, where we welcomed them and gave them jobs in our restaurant, bakery and shop. We rented them a house in Ladbroke Grove where they could promulgate Kushi's message, give shiatsu classes and teach cooking. They disdained our free and easy approach to macrobiotics and advised us to go to Boston to study with Michio. We thought they were too ‘straight.’ They wore suits, smoked cigarettes and drank Guinness and coffee just like Michio. But the rest of their diet was much stricter than ours, allowing little in the way of sweeteners or dairy products. It was a bit alienating, but we thought 'each to his own' and were grateful to be introduced to shiatsu and to have active missionaries spreading the message.

A few years ago I wrote here about our macrobiotic sea cruise. It included late stage cancer sufferers who had, thanks to Michio Kushi's teachings, been clear for five or ten years. It was moving to hear their stories and their gratitude that macrobiotics had given them life beyond their doctors' expectations.

Will macrobiotics thrive in Kushi’s absence? The philosophy is now everywhere, the basic principles of making healthy diet the foundation of your physical and mental well being; eating whole unrefined cereals; exercising actively; always choose organic; avoid sugary refined foods; prefer sourdough over yeasted breads; avoid artificial preservatives and colourings; no trans fats; eat locally and seasonally… these were once quirky macrobiotic precepts but are all now well-established and the stuff of Sunday newspaper supplements. George Ohsawa once commented that as long as you were in a state of bliss it didn’t matter what you ate, you were macrobiotic. Kushi’s messaging was more prescriptive, but it reached a lot more people. These great men are no longer with us, but thanks to their teachings the quality and variety of food we can easily obtain is better than it has ever been in human history. There is no excuse for eating crap any more. For this we should be eternally grateful.