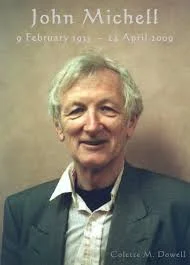

My first meeting with John Michell was on October 19 1967 after Mark Palmer phoned me from Glastonbury, where he, John Michell and a few other people were camped in a gypsy caravan in a field along the Wells Road or, like Brian Jones, staying in the nearby farmhouse. “You’ve got to come down, Craig” Mark said, “The UFOs are coming out every night, lots of them, over the Tor.” It wasn’t an invitation to be turned down lightly so I piled into my Thames van and headed down the A4 to Somerset. We got there in the late afternoon and John Michell was busy cooking up some curried vegetables with rice. He showed me how to add the spices to the oil before anything else, to diffuse the flavours so that they evenly coated and infused all the ingredients, an attention to the detail of form and function that was typical of his penetrative insight. As we sat outside enjoying the autumnal evening Mark shouted ‘There they are!’, pointing directly to the south. We looked skywards and saw lights moving across the sky. Any doubt about their being of military or aviation origin was dissipated when what was clearly an RAF jet fighter flew up towards the lights, at which point they disappeared beyond Glastonbury Tor and entered what seemed to be a cigar shaped vessel. There was a brief repeat appearance and it was over. John strained his eyes skywards but his vision was already deteriorating and he could barely make out the shapes. His first book: the Flying Saucer Vision, was being published at the beginning of the following week and he had a radio interview lined up. He would be able to say, if asked if he had seen flying saucers himself that he was in a field near Glastonbury only last week as they lifted over the Tor.

During the 1970s our family venture was the seminal magazine Seed – The Journal of Organic Living, which was variously published by my father Ken, my brother Gregory and myself. John was a frequent contributor and would drop into our All Saints Road office to share ideas and a cup of green tea. As macrobiotic health food nuts our yin-yang fanaticism was comfortably engaged by his willingness to both accept and question an idea at the same time. He accepted our philosophy but always retained a detachment that never veered into aloofness, he was genuinely interested and understanding but didn’t get passionate about the ideas we espoused. He was a warm personality but also the epitome of a particularly English type of ‘cool.’ Riding with him in his stylish old Sunbeam Talbot drophead coupe along the Westbourne Park Road could be unnerving as he peered squinting across the long bonnet when trying to traverse a tricky intersection.

He introduced me to the idea of ley lines, freely acknowledging the pioneering work of Alfred Watkins in this respect and his View over Atlantis brought the idea to a whole generation who learned to love the map of the English landscape for its natural energies, not for the roads and motorways that obscured its reality.

One of his greatest gifts, through one of his contributions to Seed Magazine, was to introduce me to the work of William Cobbett. In it he quoted Cobbett’s criticism of young people who ‘mope at the heels of some crafty, sleek-headed pretended saint, who, while he extracts the last penny from their pockets, bids them be contented with their misery and promises them, in exchange for their pence, everlasting glory in the world to come.’ He specifically targeted this quote at the tired young radicals of the 1970s who had the fire in their bellies extinguished by various yogis, Christian tribalists and other mercenary and mystic pacifiers. He also lighted on Cobbett’s “Paper against Gold” where Cobbett ‘exposed in simple language the trick by which the country had been persuaded to barter its real wealth, in labour and produce, for the illusory wealth of bankers’ promises and government paper.’ He must have smiled in his final year as the same recurring fraud was perpetrated again. John’s support for organic farming was in the lamentation: “Today less than half what is eaten in Britain is native produce and that proportion would be decimated were it not for the amounts of chemical fertiliser that must now be imported and applied to obtain any sort of harvest at all.’ In the same article: “ Cobbett conceived an ideal image of medieval England, a fair landscape, prosperous and populous, with its feasts, fairs and holidays, its profitable labour and refined craftsmanship, its equitable society giving health, happiness, security and plenty to all who wanted such things. This was the land he promised the people and he did more than any ten others would have done to keep his word and he could not/ and his failure has been the heritage of all subsequent generations.” John Michell made Cobbett’s vision the inspiration to a generation who believed that a New Jerusalem in England’s pleasant land could be achieved not by revolution, but by going out and creating an alternative society that would eventually replace the corrupt and rotten edifice of government fraud and bankers false promises. They headed for the hills of Wales and the West Country and grew organic vegetables, dreaming of Albion and founding the natural and organic foods industry and the environment movement.

This emerging change was seen to be evolutionary, but not in Darwin’s sense. In his Seed article “Towards Cosmogonic Sanity – The Demolition of Darwin” John envisaged that evolution was not a one way track, that human nature ‘has descended, not risen’ and that prophecy is about regeneration and reversion to type, not to apes but to ‘embodied spirits in union with the spirit of the Universe, citizens of the New Jerusalem.’

John was also a fierce defender of traditional measures and opposed the Napoleonic metres and grams. In Just Measure, which we published in 1976, he wrote: “The inch is the length of the first joint of the thumb, the foot stands up for itself, the yard is a stride or an outstretched arm, a furlong is the furthest distance a man is prepared to run to the pub, and a mile is the distance he is most likely to traverse on his way back. Man is the literal measure of his universe and, using such a system, he can relate naturally to it.’ He was not afraid to have a laugh while making a serious point and to illustrate the article he loaned us a beautiful etching which we captioned ‘Winchester Cathedral was built before architects adopted metrication.’

The constant theme running through John’s work was that the abolition of traditional ways sapped the independence of local society and the individual. He rejected the epithet ‘reactionary’ saying that such phrases are ‘born out of the assumption that the good of the centre takes precedence over the good of the individual…we look forward to the old criterion whereby the wealth of a nation is reckoned by the contentment, prosperity and independent spirit of its members rather than by the amount in labour and taxes that can be squeezed out of them to fuel the development of elite science, technology and culture, directed by and for the benefit of centralised authority.’ The greed of the State, exposed in the MPs expenses revelations, is insatiable. He believed ‘The Thing’ must somehow be starved.

Some commentators have slyly noted John’s frequent inhalation of cannabis as if that somehow diminished his intellect or the validity of his thinking. He would have argued the contrary, referring to the famous hand-written and illustrated manifesto of Dr. Bart Hughes, a Dutchman who wrote in 1962 that cannabis increased brain blood volume by about 40 ml above its normal 1700 ml and that LSD would increase it by 70-120 ml. Trepanation would bring a permanent relief of cranial pressure and allow brain blood volume to find an optimal level. John’s view was that the extra 1½ fluid oz (45 ml) that a good toke delivered was enough to elevate his already heightened intellect and eschewed any further resort to volumetric stimulation. Bart’s theory was based on the evolutionary assumption that our brain blood volume was restricted because, as apes, our heads and hearts were at the same level and that standing erect reduced the ability of the heart to fill the brain. John argued that we had always been erect and the lowered blood brain levels reflected our decline. Thus, pot was an instrument of regeneration that helped us rise back to our original pre-lapsarian state of consciousness. Who can argue with that without seeming frumpish and a boor?